Technological Revolutions with Jerry Neumann

I gotta say, like, I I have missed us. I I am I'm glad we're back. I'm glad no. I'm glad. I really am.

Adam Leventhal:I'm Yeah. Glad we're I mean, makes one of us

Bryan Cantrill:for sure. I missed those two. No. It's the I and Jerry, it is so great to have you here. So Jerry, we are not here to talk about founder versus investor, but we are going to have to have you and Liz back at some point to talk about founder versus investor because so Adam, do you know that the this this book that Jerry co wrote?

Bryan Cantrill:No. On okay. It's called Founder versus Investor, and it's basically a bunch of different subjects that come up at a startup with the founder's perspective, which is, Liz Salmon and and the investor's perspective, which is Jerry.

Adam Leventhal:Wait. Like, on the same events?

Bryan Cantrill:On this on just like the same concept. And This

Adam Leventhal:this sounds great.

Bryan Cantrill:It is extraordinary. It is so good, Jerry.

Jerry Neumann:We and we're still friends after writing it together.

Bryan Cantrill:That's the previous And and you should just be totally good. When I say it's so good, I mean, what Liz says is so good. I mean, obviously, what you say is, you know, yeah. Of course. Of course, you would.

Bryan Cantrill:You know?

Adam Leventhal:Jerry, are are you of a vintage to know this Roseanne Barr, Phil Hartman sketch called MetroCard, where it's like it's like a a person with a credit card, like, calling customer service. Do do you know this sketch?

Jerry Neumann:I don't I'm I'm I'm I'm sketched.

Bryan Cantrill:I don't know it. Yeah.

Adam Leventhal:Okay. Anyway, so it's like Roseanne Barr being very shirty and telling Phil Hartman basically he can shove it where the sun don't shine. And Phil Hartman says, she gave me several options.

Bryan Cantrill:She gave me a lot of options.

Adam Leventhal:And I and I feel like, you know, there there might be moments in that in that founder relationship with the investor where where it kinda feels like that on on different sides.

Bryan Cantrill:The book is and it is also, have already Jerry, I've already read passages aloud to my cofounder. And, I mean, it is laugh out loud funny. And some of these passages are just like, oh my. Is that actually in the book? Like, that's that you mean, that's what happened to us.

Bryan Cantrill:But I'm like, no. No. No. It's actually it is actually what's in the it's very good. Anyway, it's extraordinary.

Jerry Neumann:Parts to me and the stuff that is that actually in the book or Liz. Right? That's

Bryan Cantrill:I you know, just love the way it's constructed where you got I mean, because and she is definitely like she's, you know, she's sassy. It's great. I mean, just for lack of a better word. She's and she's very funny. And Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:I actually think that and then but I actually love because your, your sections are very, boots on the ground. I think they're they're very clear eyed. I'm sure funny as well. I feel like this is coming across as a criticism, and didn't mean that. I'm sure there's there's much humor in your sections as well.

Bryan Cantrill:Funny, damn it. That's right. But no, it's it it it's also I just I love the fact it's a great idea because I think that what you were trying to get at is like, look, there's not one truth in a company. Like, there can be multiple truths and here are different perspectives. And I also love the the bits you agree on.

Bryan Cantrill:So great book. Yeah. Everyone should read it.

Jerry Neumann:I mean, it really would you read the other books written by people and it's like, well, let's find the middle ground. And I think in in real life there sometimes isn't middle ground, you know? And you just need to know that.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. And then you do have the things where you both have found the middle ground. Like, that's in some ways, like, the stuff that is, like, really gold is where you and Liz both agree on, like, no. These are the things we agree on. Like, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:That's, like, correct. This stuff. Anyway.

Jerry Neumann:Yeah. Although there there were definitely times in the writing where she would say something and, you know, while we were writing, I'd say, can't say that. I'm saying that. And she's like, oh, you're right. I'm like, gotta see the other side.

Bryan Cantrill:You gotta see the other side. Yeah. That that is great. Well and clearly, I mean, it built on because I mean, you invested and I've not read the entire book. I've only been I I it arrived and I kinda agree, picked out a couple of passages and then was laughing out loud and, you know, I need to actually properly sit down and read it.

Bryan Cantrill:But you invest in her, is that right? You, she would, you have a relationship from actually having a company?

Jerry Neumann:Yeah, no, I invested in her first company, I think I was one of the, probably the first professional investor, invested in her second company. And then I've now invested in her third company. Yeah, no, we've had a long, I've known a long time.

Bryan Cantrill:Is great. Well, in translation, she's made you some money because I did, when when, at a previous company, I was going in with the the CEO. We were trying to raise money and lowers a lot of hair on the company, so it's hard to raise for. It's like, this is gonna be a pretty easy conversation. Like, oh, why do you say that?

Bryan Cantrill:He's like, I made these guys a lot of in a previous gig. And we went in and I'm like, that was a really easy conversation. He's like, well, yeah, once you've made but that that's how we end up with the melt. The melt was you remember the melt? The sandwich?

Bryan Cantrill:Of course. Yeah.

Adam Leventhal:The venture backed grilled cheese.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Sequoia backed grilled cheese because the guy made all the money on the on flip flipping flip ironically to Cisco for, like, $6.41 or something like that, Adam. It was just crazy.

Bryan Cantrill:Remember that? They and you're like, like, why did Cisco buy Flip? Do you remember Flip, Jerry? These are the the video company. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Right. The do I? I was on the cap table. Those guys made me admit. Right?

Bryan Cantrill:I was in on the melt. I was I was the first money in on the melt. That's you

Jerry Neumann:know, I have to say Liz's new company is not the melt. And, you know, she had a few, when she was ideating a couple of ideas were kind of like, you know, maybe not that. In the end she had something, but it was, I would have invested in anyway.

Bryan Cantrill:Well, that's so actually, that's kind of interesting because and so Adam, you and I have a shared acquaintance who was in the third company of someone who had had two outsized successes. And he was like, this is great. Like, this guy, like, he's had two outsized successes. I'm like, the third company is danger zone because he thinks it's not that hard. I mean, maybe he wouldn't say that, I'm sure, but at some point in his heart, he's like, this isn't that hard.

Bryan Cantrill:I've done this twice. I can do this again. And it's like, no, no, the third one is the one to be like the immuno the the immune system has been suppressed. And that was Impact Crater, I believe. I don't know.

Bryan Cantrill:I think I think I think it was a zero, that particular company. Yeah. Put You

Jerry Neumann:a little bit of a chip on their shoulder, I think. Somebody who really needs to feel like they need to accomplish something. And

Bryan Cantrill:that's Liz

Jerry Neumann:still have yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:There you go. Liz is still still hungry. That's terrific. Quite a great book. We're gonna have to about that in another time because that's actually not why we're here.

Bryan Cantrill:We're here to talk about this twenty fifteen piece that you wrote that was on the deployment age, which was pointed out to me, by a by a listener to the podcast, I think is I think is here as well. But the, I had discovered I and don't even know how I discovered it. I I was or how I hadn't discovered it earlier, frankly, Carlo DePerez's book, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital. And Jerry, I gotta tell you, when I read this book, I'm like, how have I not read this book? I've not encountered this before.

Bryan Cantrill:And it was, like, very thought provoking. I don't agree with all of it, but it's very, very thought provoking. And then I was I was pointed to your piece, which is like, okay, I'm not the first person to discover this. How did you discover Perez's work? Am I the last person on earth to discover this?

Bryan Cantrill:I I I just, again, I don't know why it's taken me this long.

Jerry Neumann:No. You know, it's actually super interesting. Right? Because I I was just talking to to my wife about this and she is not canon. Right?

Jerry Neumann:It's not economic canon. All the Shumpetarians are out of canon. Know, the twentieth century was completely like the mathematization of economics of, you know, steady state, you know, figuring out where supply meets demand and saying, that's where we go and not talking about change because change is too hard to fit into the framework that they were still building. And yet people like Schumpeter who were like, well, okay, but none of this is true, right? Because if things keep changing and then, you know, she and the mainstream of economics said, okay, that's true, but we're not gonna talk about that.

Jerry Neumann:Like, that's we're not allowed to talk about that. And that's not maybe not entirely fair, but it it it is primarily true that the mainstream economics doesn't talk about doesn't like to talk about change. And this is where it comes to me. I just

Bryan Cantrill:yeah. It's true. Right? I actually thought something was canon. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Mean, he's probably the biggest thing that was yeah. Yeah. But Interesting.

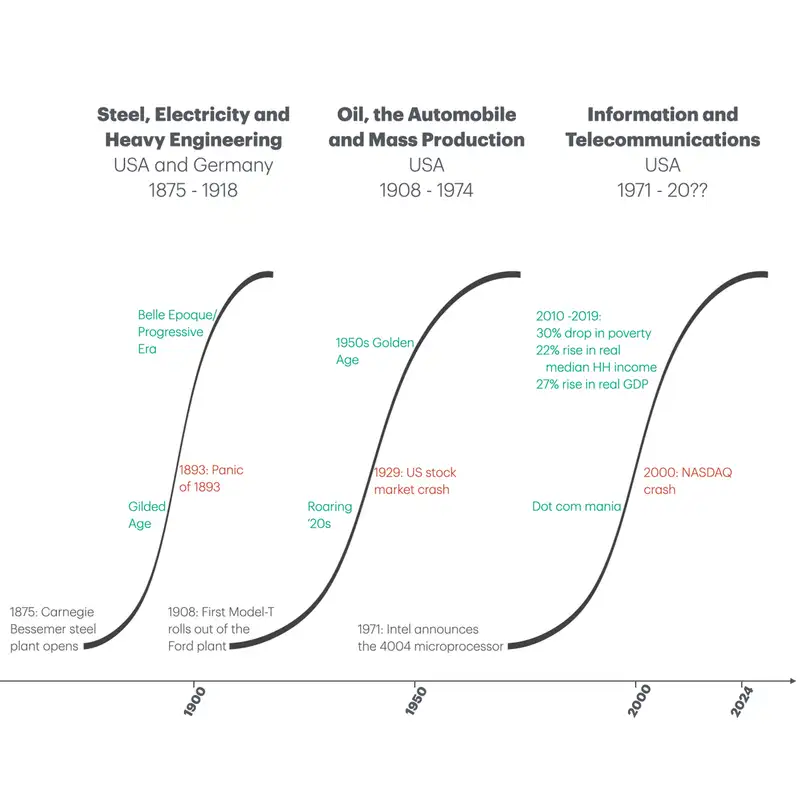

Jerry Neumann:It's not like but yeah. No. So she the the the idea that there are these kinda long waves of technological change that she describes is an old idea. I mean, they're they're called kundradiative waves from this Russian economist from, like, I don't 1920 or something, who noticed that there are these ups and downs in, not in the economy per se, but well, in the economy and in what's driving the economy to grow. And so, oh, he kinda said there are these sixty year waves.

Jerry Neumann:And economists since then have taken that idea and given it more body. And she was one of the first to really put together a convincing and sort of holistic explanation of why this would be so. Because like, you you think like, well, why sixty years? Like, is there, there's no like clock on the economy, right? Like, why isn't it twenty years or eighty years or something else?

Jerry Neumann:And, you know, why why are these waves at all? Why aren't why isn't it steady progress? So this is the she writes about this book as an explanation. And and I don't think it's a mainstream book, so no, you're not the last person to read it. I think most people haven't read it.

Jerry Neumann:And if you brought it to, like, your economics professor in college, he probably hasn't read it.

Bryan Cantrill:I'm not really on speaking terms with my economics professor in college. I think we we both agreed to disagree on a lot of things. So I think we both agreed that we actually in fact did not value one another's perspectives, and maybe it was time for us to go our separate ways. Right. But so and what she describes is this kind of the the this you have this early eruption, eruption with an I, where you have this kind of explosion of you've you've some big bang event that that opens kind of a a new frenzy, gives way to this this frenzy of allocation of capital that if you get too much capital effectively, which she calls financial capital versus production capital.

Bryan Cantrill:And I gotta tell you, I thought you did a much better job of explaining the difference than than she did in her book, because it as you described in your piece, it it took a little while to internalize what she meant by financial capital versus production capital. And you had this crash where then after the crash, it's more production capital than financial capital. Do you wanna describe that difference a little bit? Because I I think it's they're kind of strange terms, and it kinda how you redefine them a little bit.

Jerry Neumann:Let's let's take the information technology communications information communications technology revolution, which is the one that we're in now. Right? And and she says, like, alright, this started in 1971 with Intel's release of the first real microprocessor, the 4,004, and it starts off slow and people don't really see the use of it, of this new technology. They they you know, it may be an interesting technology, but they don't think that it's gonna change the world. Nobody thought that about the 04/2004.

Jerry Neumann:Even, you know, even after Apple was founded, people weren't like, oh, personal computer is gonna change the world. Some people said that, right? But though, you know, and now there's kind of this selection bias where we go back and we're like, oh, look at these people who knew was gonna happen. But most people didn't, you know? If you look in the New York Times and search for personal computers in the 1970s, they mentioned personal computers in all of its different, you know, names, home computers, you know, portable computers.

Jerry Neumann:They mentioned them like eight times. Like, it's just nobody's paying attention to this for years. Right? Because it's it's not making a difference yet. Like, there's nothing you could do with the the Apple two computer besides play games.

Jerry Neumann:Like, nobody did anything with it. No one said you could have. Right? But but nobody did. Nobody's running a business on an Apple two, except maybe a couple crazy people.

Jerry Neumann:So it wasn't changing the world. But at some point, people started to say, hey. You know, I can see where this might go. What where this might go. Right?

Jerry Neumann:And and you get the some venture capitalists coming in and saying, like, in this era, venture capitalists, in previous eras it was different sources of capital coming in and then saying, you know, this could be big. This could be really big and I'm gonna bet on it. And, you know, she calls it more of a casino, like their people are taking huge risks in the hope of huge gains. And this is financial capital. Right?

Jerry Neumann:The the financiers, the venture capitalists in this wave come in and say, hey, we can make this technology more productive. We can make it more useful by spending money on you know, putting money into companies that are gonna make it a better technology and and bring it into places where it hadn't been before. And this is really, you know, this is so that that's the financial capital part. And this is why it leads to, the frenzy, the like, the .com bubble, because, you know, the the the financiers who are making bets don't have a lot of information to go on, right? Don't know, right?

Jerry Neumann:They don't like, you know. Mean, would you have invested in Apple when Apple started? I mean, about it, right? Mean, it's easy to say yes in retrospect, but when you go back and you look at it from as if you were there at the time, I mean, you know, Steve Jobs, like, you know, his long hair, shoes, smelled.

Bryan Cantrill:I mean,

Jerry Neumann:no job. Why would you invest

Bryan Cantrill:in When you talk about the selection bias, it's like, it's also like, you've got to remember how many different computer companies there were in 1981, 1982, 1983. I mean, there were there were so many computer companies and some of which had seemed much more promising than Apple. So it's a little unreasoned to think that you, you know, one of the one of the the companies that that we always view as a cautionary tale is Osborn. And because Osborn actually had product market fit and but ultimately, went out of business because they operationally failed. They they literally bought the wrong stuff at the wrong time when they were and they just went insolvent, and it happened very, very quickly.

Bryan Cantrill:So yeah. Absolutely. You cannot kinda retcon. I I mean, there were scores.

Jerry Neumann:Right? Scores.

Bryan Cantrill:And then so so then you have this crash, and then Yes. And so and then after the crash and the kind of the embers of this the the the kind of the the nuclear winter that follows one of these crashes, you begin instead of having financial capital, you have what she calls production capital. Yeah. And how do you I I actually liked your definition of production cal, because I don't think she redefined it very well. And I think it was actually very helpful to have you kind of catalyze that.

Jerry Neumann:I I I did because I read the book and I'm like, what does what is she talking about? So I I tried to explain the things that I didn't get. Yeah, no, so you have, during the first part, when it's financial capital, all the money's going into building the technology, trying to make the technology better. But then when there's the crash, the financiers tend to kind of step back a little bit and say, Hey, all right, you know, we kinda got out over our skis, took too much risk, we need to be a little more careful. Usually the government gets involved and says, All right, you guys just lost a lot of people, lot of money, and we need to make some regulations, which happened after the .com crash, right?

Jerry Neumann:And so things tend to get a little calmer. And also there are now big companies, right? Because they use this money from boom to become big. And these big companies have money, but the big companies don't aren't gonna take crazy risks. Right?

Jerry Neumann:They're gonna try to build their businesses. So they're gonna use their money to say, how how do we become a better company? How do we become a bigger company? How do we take more market share? How do we provide the things that our customers are asking for?

Jerry Neumann:Or that we know that our customers need as opposed to, you know, Apple, which nobody was asking for, you know, well, there were like 10 people asking for a home computer. Alright. 10,000 people asking for a home computer, but there wasn't a market, Right? Nobody was asking for the Apple two. Nobody was asking for the Apple one.

Jerry Neumann:But, you know, Google, when they put out, you know, Gmail, they're like, people need this. Right? This is something that people need. Right? So they're spending production money, production capital to make their own businesses bigger.

Jerry Neumann:This is like they're they're I've written elsewhere a lot about, like, knighting uncertainty, the idea that there are some things you can't predict. These are things where they felt they could predict with some sort of not certainty, but they could they could roll the dice. Right? They could say, like, this is a good bet. We're gonna make money on this, you know, 50% of the time.

Jerry Neumann:It's a rational decision versus the financial capital sort of, not really rational decision, It's the animal spirits thing. So the production capital is all rational decisions.

Bryan Cantrill:So I've got okay. And here we are here we have arrived at Brian hot take number one. I've got many hot takes, by the way. But this is my okay. So here's my first hot take.

Bryan Cantrill:So my first hot take is from having been and Adam and I just for full disclosure were have been on the inside of big companies. We worked at Sun Mic I was at Sun Microsystems for fourteen years. Adam and I were at Sun together. And we convinced Sun to to to start something wholly new that became a billion dollar line of business for what was that Oracle, sadly. But we so I so I actually don't think I I think that the distinction is actually a little bit different.

Bryan Cantrill:I actually don't think the distinction is around risk. Because I think inside of Google, I think Gmail nobody thought Gmail was gonna become what Gmail is today. I I really I mean, folks can correct me if if they're they're an inside and they disagree. I don't think inside of Apple, I don't think anybody thought that the iPhone I mean, yes, you you know, you kind of have this, like, abstract vision word. This is what what it could be.

Bryan Cantrill:But in this, again, my hot take is that the fundamental difference is that that production capital is not building to flip. Whereas venture capital is building to flip. I've got to find a buyer for this thing, and I've got to find buyer, by the way, like, within ten years or within within five years if I'm SoftBank. I gotta I gotta be in and out in five years. And when we started, we started this, it it the term gets denigrated, but I like it, an entrepreneurial effort inside of Sun that we called Fishworks.

Bryan Cantrill:And I always viewed it as like we had one investor, but that investor on the one hand, like we had to to deal with, you know, some of the the organizational battles. Adam remembers very well. But we but that investor honestly had a very long time horizon and didn't really have to have contentious board meetings about not hitting targets. We so the the I actually think that the the the there's still uncertainty there, but the risk tolerance is really different. And you can actually do something riskier when you are inside the confines investing production capital.

Bryan Cantrill:That's my feel free to disagree, but that is my that that is that is hot take number one on this.

Jerry Neumann:Well, what what year was that?

Bryan Cantrill:That was in 2006 that we started that. Okay. So the 02/2006, we believed that we could be a billion dollar top line within four years of shipping a product. We shipped our first product 02/2008. Oracle, sadly, this is where I've got some degree of culpability.

Bryan Cantrill:Listeners to the podcast like to create their own bingo cards, by the way. So you've got people who have just been able to check off Oracle off their bingo card. They're really elated. The sadly, we were able to attract Oracle as a customer to Sun for the first time in in half a decade, which is basically like taking a severed tuna and and waving in the water. We were basically chumming for an apex predator.

Bryan Cantrill:And all of a sudden, the dorsal fins of of Larry Ellison appeared and ate the company. So I've I've always felt like some degree I'm not sure if I confess it here or not, Adam, but I've always felt some degree of culpability that it was our own.

Adam Leventhal:I I don't know that you've even confessed that to me. I didn't know that you felt like Fishworks accelerated No. You by the predator.

Bryan Cantrill:You remember the Oracle deal that we we had a huge Oracle deal as Fishworks. You know, I've that. No. I forgot about that.

Jerry Neumann:But you

Bryan Cantrill:remember it now that I mentioned it. Yes. Yes. Very technical customer that was very, very interested in Fishworks, and they had, like, outsized ambitions for us. It was great.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. It's like, oh, this is great.

Adam Leventhal:Oh, it's be great. Too outsized. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:This could be great. It's like, woah, wait wait a minute. Why are you why are you so close to me? This is a little uncomfortable. What are you doing?

Bryan Cantrill:Why are you opening your mouth? But, yeah, it always felt like, oh, man. I should not have because in that whole drama. So, Jerry, they there there was a bidding war between HP and IBM, each trying to one sabotage the other, and two, they each wanted to pay the least amount as kind of to to kind of like denigrate and desecrate frankly an old competitor in Sun. So they reached basically screwing around with the deal, and then Oracle swept in and and bought the company.

Bryan Cantrill:Oracle, a 100. Oracle a production company built around financial capital. I say financial capital company for sure. They do not care. They do not have the same disposition as Sun.

Bryan Cantrill:But so I would think of the iPhone is the same. It'd be interesting that like inside of of Apple I mean, because the iPhone was given I mean, I and I I think I've said this here, Adam, but, when the iPhone came out, I was a detractor and I was not alone. I mean No. Adam, you were not a detractor and I feel it was a more loneliness position for you.

Adam Leventhal:I think that's right. Well, you certainly made it feel though. No, I know it's insufferable. During those fish Let's

Bryan Cantrill:spit Diet Coke on the mic again.

Jerry Neumann:I mean, I think this is look, you know, companies are run by people, right? Steve Jobs coming back to Apple after having been fired and having to prove that he was going to grow this company again, had him take more chances than anybody who, if what's his name, it stayed at Apple and run Apple, right? So I think it's wrong to treat this kind of theory like Perez's theory as science, it's not science, right? This is a description of things of a process. And I do think like, anecdotes aside, if you look at the overall business climate today or ten years ago even versus the corporate business climate in the 1990s, you see a big difference in the kind of risks people are willing to take.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. That's interesting. And it was so good. Okay. So I wanted let's take that apart.

Bryan Cantrill:Because I definitely agree with you about you've gotta be really careful. And actually Perez herself warns about being overly prescriptive with her theory. She's got a great paragraph about it shouldn't be a straight jacket. And then she can she proceeds to kinda stitch a straight jacket together, frankly, for the rest of the book. So, there's, like, a little bit of a duality in there.

Bryan Cantrill:But so, Jerry, one of the questions I have for you is, you know, she cuts these kind of big you know, these five big waves and then tries to, apparently, as recently has said, like, no. No. The information and telecommunications boom that started in 1971, we are not yet in the crash. We are still in the the what she calls the installment phase versus the deployment phase.

Jerry Neumann:Totally. And I completely disagree with her. Completely I

Bryan Cantrill:a 100% disagree. Come on.

Jerry Neumann:Yeah. Like, how can go? But I mean, the interesting thing, I completely disagree with her, I know I'm right, and she's wrong. I also realized that, you know, she's probably smarter than me. So what that tells me is like, it's actually really hard to see when you're in the middle of it, you know?

Bryan Cantrill:I agree, yeah.

Jerry Neumann:So, know, is she wrong? Well, yeah, she's wrong, of course she's wrong. But I'm sure that's what she'd say about me. I don't know, you know, once you get into the production capital phase, things change, right? Like in the part when it's financial capital, there's a lot of money being spent on building the technology, but the technology is not being used in ways that create more productivity and thus economic growth so much.

Jerry Neumann:And this was, you know, there was always the economist wailing about how the computer wasn't showing up in the productivity stats from 1980 until February, right? The computer's everywhere except in the productivity stats. Interesting. Right? And, but that's all, that was all somebody who was in, oh, David wrote, what's his first name?

Jerry Neumann:An economist's last name, David wrote an article called the Dynamo and the Computer, I think that's the name and talked about how during the technological revolution around electricity, the same thing happened at the beginning when dynamos were being installed. People were spending money on installing dynamos and improving dynamos, not on using the dynamos to create productivity. So that was where the money was going, right? So you didn't see a lot of, like TFP growth. So, but then after the production capital takes command, not complete command, but overall command, they start saying, well, can we make more money with this technology?

Jerry Neumann:And the way you make money is by putting it in way out in ways that makes customers' lives better, right? So it make, somehow you're creating more, you're creating this economic growth and and that's why people are buying it.

Bryan Cantrill:And and Totally.

Jerry Neumann:And what should happen then is you're gonna see the the the value that's being created spread more widely to more people in the economy. So, you know, after World War two, in the last wave, you had, like, the nineteen fifties, which was, you know, the golden age. Right? Where the the value being created by the technologies, the the the automobile mass production, gets spread more widely throughout the population, or at least the population that was allowed to take part in the economy, and and their lives became better. So that should be the sign that you're already in this second half deployment phase.

Jerry Neumann:And and I think we saw that. Right? I mean, you know, if you I put in this chart that I just put in in the chat, like, if you see look at 2010 to 2019, there was actually amazing economic growth, and people's lives were getting better even though we kept we you know, everybody was telling us that everything was getting worse. You know, there's a lot of propaganda around that. In fact, you know, life in this country was getting better for the average person.

Jerry Neumann:So that to me is a sign that you're in the second half where the technology is being rolled out and being used in ways that makes people's lives better, not still in the first half where people are working really on making the technology itself better, not using it in ways that, you know, are productive. So I'd absolutely see how we can't already have been in the deployment age for at least ten years now.

Bryan Cantrill:I think we've been in deployment age for at least ten years. I think and then that deployment age then did what I mean, I think what she rightfully points out that that happens when you get deep into the deployment age where then the these very large institutional entities that we've relied upon to allocate capital post the crash and have done so effectively gives us I love your Gmail example. Gives us Gmail, gives us the iPhone, gives us Facebook prior to 2012, gives us Facebook when it was uplifting for people. Right? Gives us kind of early social networking.

Bryan Cantrill:There's a bunch of stuff we have. And I love this conference that you presented at, that you originally presented this work at, Transition in twenty fifteen. So the the site that you linked to is gone, so I had to go to the Internet archive to find it. But it's kind of mesmerizing. I don't know, Jerry, when you last looked at the agenda for this thing, but you go back to and you just realize that, like, wow, 2015 was a long time ago.

Bryan Cantrill:And this is because it this there's this whole idea of, like, you know, we are gonna create the global middle class and and, you know, the lives are getting better and we're in transition to, you know, software is gonna rule everything and it's and that's gonna make everything better and uplift everybody. So one of again, Brian's hot take number two, and, again, there could be many of these, is that the revolution that Perez often predicts. I I think that that may have been the twenty sixteen election where the there's this kind of and you also have I mean, during that, think that you can argue that there are a couple of different shocks in there. I do think it's a that that a lot of these big institutions very much lost their way. You have, Facebook obviously lost its way.

Bryan Cantrill:And, I mean, there's one by one, these kind of companies. Google originally sets out as don't be evil is like the kind of tongue in cheek motto of the company, and then becomes like the legalistic bar that they use to apply to their own actions. Mean, no. No. Like, that wasn't evil.

Bryan Cantrill:I was only super shady. That was not actually evil. That's fine. It's like, no, that's actually not what you were. That was not what don't be evil meant in 02/2004.

Bryan Cantrill:That's not what it meant a decade earlier or a decade and a earlier. So I I actually wonder I totally agree with you and agree that that that press is wrong. That revolution clearly, but we did see all of this late stage stuff. And one of the late stage things I wanted to ask you about is this kind of perversion where production capital becomes financial capital with buybacks. And you have these dividends from the dividends, lowercase d, kind of believe the the profits from the iPhone, the profits from Gmail, instead of being and these companies have changed, they'll pay out proper dividends, but they would actually use that to actually buy back their own shares.

Bryan Cantrill:Is that production capital becoming financial capital?

Jerry Neumann:Well, is, you know, is there's so many interesting questions that Perez doesn't answer. And I think because this isn't mainstream economics, you don't really have, like, people who wanna become professors writing about this. Right? But, yeah, no. Although, I would say that, you know, if you think about the nineteen sixties, which was the end of the last wave, and you think about the financial markets from the nineteen sixties into the nineteen seventies, I mean, the nineteen seventies were an awful time to be an equity investor.

Jerry Neumann:Like, there was just nothing was happening. There was, like, no reason. Like, right? So that was when people would you think back to the nineteen seventies and, you know, not that I remember the nineteen seventies that well, but, you know, it was the bond traders were like the BSTs on Wall Street. Right?

Jerry Neumann:And it bond traders, like, really? And it's because the equity was nothing. And the big companies pay dividends, which dividends and buybacks are the same thing. Right? I mean, essentially, Besides the taxes, they're the same thing.

Jerry Neumann:So they what happens is as the market starts to get saturated. Right? You like, the computer market is now pretty saturated. There's not a you know, everybody's needs are being taken care of. There's not a lot of new needs that you know, if you're gonna if you're gonna build something new that is a computer technology, you're probably gonna take money from some other computer technology company.

Jerry Neumann:Right? It's it's it's just there's no more market to grow into. So what is happening

Bryan Cantrill:Is is now we reference back to our previous episode on raising our $100,000,000 series b? Definitely not from from corporate venture capital. Yes. Yes. I I understand I understand the point you're making the abstract.

Bryan Cantrill:The current company excluded, of course. But

Jerry Neumann:yeah. But so what do you do if you're Google? Right? Where are you gonna spend all that money? Like Yeah.

Jerry Neumann:You can't you can't invest it all if if it's production cap. Like, there's just not enough productive things to invest in. So you're gonna do stupid things like start Google Ventures. Like, not that Google Ventures is stupid. It's know, some really smart people work there, but it makes no difference to Google.

Jerry Neumann:Like, how much money can Google Ventures make that would change anything at Google? Like, it can't. Right? It could have the biggest outcome in the world, and it would wouldn't change Google's earnings by anything. Nobody cares.

Bryan Cantrill:I I mean, have you have you I presume what you've dealt have you co invested with GV or dealt with GV? GV is like GV truly loves to have it both ways because you're like, are you Google or are you not Google? And they're like, well, what do you want the answer to that question to be? Yes. Like, if you if you want us to be Google, we are absolutely Google.

Bryan Cantrill:But no. No. If you don't want us to Google, that's why we're GV. There's not even Google's not even in the name, it's GV not Google Ventures. They're really smart

Jerry Neumann:people who'd, you know, wanna go somewhere else. Right? It's like, oh, do do this instead. Yeah. I mean, seriously, they could be Sequoia and it wouldn't change Google's earnings.

Jerry Neumann:Right? I mean, barely. Right. So, you know, it's not, that's not, it is financial capital, but that's not what's happening, that's not the story, that's not the show. The show is, you know, Google makes a shitload of money, what are they gonna do with it?

Jerry Neumann:Well, they could pay dividends, but that's not the thing people do these days because it's tax inefficient, so they do buybacks.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. And and I think

Jerry Neumann:you know? But it's not that's not financial capital because they're not making bets on things that are you know, these crazy bets. Right?

Bryan Cantrill:So the other thing I know? I wondered about is, you know, Perez draws these kind of huge waves and wants to have, you know, only, I guess, only five in her lifetime. But the I mean, I I think it's actually more instructive, or to me, was more valuable to think of it as smaller waves, because I feel in my career I mean, I mean, there was a PC frenzy in the early eighties that collapsed and changed and and and you got investment capital changing from financial capital to production capital in personal computers. That happened in software in the later eighties. That happened in the Internet, obviously, with the .com bus.

Bryan Cantrill:I mean, it's like when I look at these kind of smaller things, because, like, mobile I I view mobile absolutely was a frenzy and a crash where and in fact, the the Andreessen's software's using the world piece in 2011 is is actually written at the peak of that mobile frenzy. I don't know. Jerry, one of the last time mean, also, like, look, I'm

Adam Leventhal:It's our favorite, party trick here.

Bryan Cantrill:It's our favorite party trick.

Jerry Neumann:It is our favorite

Bryan Cantrill:party trick. It is the software's eating the world written in 02/2011 by Marc Andreessen. It's like, okay. Well, software's important. Thank you for that's such a high thought.

Bryan Cantrill:Who who who who that? The but Andreessen does us the favor in 2011 of telling giving us example companies that that are are the exemplars of software devouring the world. Do you know what those companies are?

Jerry Neumann:Are any of them still in business?

Bryan Cantrill:That's a great question. That is a question for the the the for the investors or or debt holders of Zynga, Foursquare, Groupon, Living Social, and Rovio. Those are the five companies in Ames. Yeah. How have you pulled off the magic trick of people like, this guy is such a genius for this essay.

Bryan Cantrill:It's like, could you read all of it? I mean, it's like you would literally be much better. I mean, like, no mention of Nvidia, obviously, it's 2011 Nvidia or AMD or even like I mean, just there are lots of companies that are anyway. So You know, it's funny.

Jerry Neumann:Right? Because they just

Bryan Cantrill:That reflects its tone. Very good. That reflects that that it would that reflects those companies actually reflect the apex of a frenzy around around mobile. Right? That's Zynga, Foursquare, Rovio, LivingSocial, Groupon.

Bryan Cantrill:Those are like the companies where mobile is eating the world. And they're all wrong because there is a crash and those companies actually don't have the staying power.

Jerry Neumann:Yeah. I mean, I think there was So I think there's two points I wanna make here. One, I totally disagree with you. And two, I'll get to that one in a minute because it's longer. But two, I think it's, he was both early.

Jerry Neumann:I mean, it's funny when he said that it was obvious, right? I mean, software's in the world. Of course it is. And if you had read Perez, you're like, well, yeah. I mean, that's the books about that, right?

Jerry Neumann:That this technological wave is going to change all of society and remake society around itself. And you know, in 2015, I put some predictions in the deck, which people come back to me like, wow, those predictions really came true. I'm like, yeah, I was kind of thought they were silly when I made them because it was already obvious they were gonna happen, right? But I also think he was a little early because he was still in the part where things hadn't quite settled down yet, right? I mean, it was still the beginning of deployment.

Jerry Neumann:Other one, the part where I disagree with you is, yeah, there's definitely different waves. I mean, and I make this point sometimes you look at the chart of Moore's law, right? Moore's law, S curve, mostly exponential for the most of our lives, maybe flattening out a little bit now arguably. But if you look at that underneath, it's like one big curve, right? But if you look underneath at the underlying technologies, you know, optical lithography was definitely peaked and then went away, and then you had, you know, X-ray lithography.

Jerry Neumann:Mean, like, there's a bunch of different technologies that built into this bigger wave, And I think what she's saying isn't that there aren't different technologies that take part in this one big wave, that because she's not talking about technology per se, she's talking about changing society, right? How technology changes society. If you go back to like the industrial revolution, the first one, yeah, mean there were like water driven looms, right? And that changed things a little bit, but then there were other things that used the same sources of power like water driven automation of tasks that used to be completely manual, And those together were the big wave that changed things. And the reason I disagree with you, I feel like I have to disagree with you and is because the financial capital slash production capital thing is all consuming, You can only pick one wave at a time because there's only so much money and there's only so many people.

Jerry Neumann:So even if like in 02/2005, the technology that was gonna kick off the next wave appeared, nobody would have backed it because they were busy backing this wave. So you look at, like, the first computer companies. Right? Like, the Eckert Malkley computer company I mentioned in that post. When they launched in, like, 1949, 1950, it was the first mainframe computer, like, commercial mainframe computer.

Jerry Neumann:Nobody would fund them. Nobody would give them financial capital because they were busy with the previous wave. They were busy funding things like car companies and, you know, mass production, you know, plastics, this stuff. Right? So they couldn't raise money.

Jerry Neumann:They had to they basically had to sell themselves. You know, IBM had been around for almost a century by then in in its various forms. All this stuff was was rolled out as production, not financial. You can only have one wave at a time. And I think it's

Bryan Cantrill:two point maybe in the middle of panel,

Jerry Neumann:we can start new one.

Bryan Cantrill:So I'm I'm gonna give you a counterpoint to that. And the counterpoint is going to be that so you talk about the Eckermannockle, you also talked about about DAC in the piece, and deck funded by George who in in in some regards is, is kind of the first venture capitalist. But I I I I think that that's a bit of a of a misread because there's no line from from George Dorio to Silicon Valley VC. And when and so Pierre Lamont, who was at was at Fairchild and was actually on Oxide's board, which is terrific. The Pierre tells a story of how they wanted to leave Fairchild and start a company.

Bryan Cantrill:But this is in in 1967. VC doesn't really exist, and they had to go find a public company, take it over, and then raise money using the the vector of being a public company, and that was National Semiconductor. Based on the success of Nat Semi, that was where the Intel got true proper I mean, Intel is basically the first, I would say, real even though you Deck, yes, had a venture deal as you pointed out. It's like Deck is a portfolio maker. He had a bunch of zeros because it was such a ridiculous deal for the Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:For for the investor, terrible deal for the entrepreneur. As you say, the ultimate entrepreneur got the ultimately worst deal in the the the history of deals. But the the when we actually get true proper venture capital starting with Intel and then beginning, like, growing very slowly through the seventies and kind of exist in the seventies doesn't really become, I would say, mainstream investment vehicle. I mean, mean, you're the you're the VC, but I would say it doesn't really become mainstream until the nineties. Maybe even until later than that.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, no. No.

Jerry Neumann:Oh, okay. I actually wrote a post about this as well. Sorry.

Bryan Cantrill:No, no, no, you think it's mainstream earlier than the nineties or you think it's mainstream later than the nineties? Because I think I can find VCs who would argue both directions. Yeah,

Jerry Neumann:no, I wrote this post called Heat Death about venture capital in the 1980s. Yeah, That was probably my most read post. And it talks about the seventies and the eighties and the venture capital, but I mean, you're right. It like didn't, you know, venture capital didn't really get off the ground until the late sixties. And the first venture capitalists were like going door to door looking for small companies to fund.

Jerry Neumann:It wasn't what we would call venture capital at all. And it you

Bryan Cantrill:know, it's something attracting, like, sovereign wealth funds. Right? I mean, when when do when you get start getting, like, really much larger pools of capital pointed towards Silicon Valley. So here's my my question for you slash hot take. Hot take number three slash question is I wonder if the presence of venture capital doesn't serve to absorb a lot of these booms and busts because we end up with these micro frenzies that then bust out, and there are lots of these.

Bryan Cantrill:We can talk I mean, like, you certainly get I mean, obviously, ones like web2.0 and crypto, but also, like, I think they called it micro mobility, whatever name they came up with for scooters. Right? I mean, that was there was a brief VC frenzy around scooters. And I remember, Adam, I can't remember if told you this or not, but the first time I wrote a lime, I feel like I could see the whole thing in front of me because I could see that, like, this is going to be VC catnip because it is capital that is just making money. It's just capital that like is like there's no labor, I had an app, I walk up to it, I like used it for ten minutes and it got money and that is just gonna be catnip for VC.

Bryan Cantrill:And yet, I could also see, like, also, I think they're gonna get thrown into Lake Merritt. I think they're gonna be stolen, locked in garages. You know I mean? You're just like

Adam Leventhal:You're thinking this as you throw it into Lake Merritt yourself.

Bryan Cantrill:I'm thinking as I chuck it into Lake Merritt, I'm like, you know where this one's going? Bottom of the drink. Give me another VC funded scooter, I say. But the and this was this and didn't have the staying power to so but VC absorbed that. Like, the public didn't wear that boom and bust.

Bryan Cantrill:The the the public wore the .com boom and bust in a way. I again, that's a hot take slash question. Hot question? I don't know, Jerry. How delusional do you think that is?

Bryan Cantrill:But that venture capital has served to absorb some of these.

Jerry Neumann:You know, I recognize that I am too close to what venture capital should be just because that's what I did for so long. And, you know, I had a lot of disdain for some of what venture capital is or was at different times. So it's a hard question for me to say, but I I know we're not talking about AI, but, you know, is people putting a $100,000,000, you know, writing a $100,000,000 checks into AI companies, is that venture capital? Right? I mean, are they really taking a bet on this or do they believe that this is a foregone conclusion?

Jerry Neumann:Right? Think, the interesting thing, when I gave that talk ten years ago, I said, the funny thing about Perez, because VCs love Perez, like they love talking about Perez, the thing that Perez says, even then,

Bryan Cantrill:Chris Dixon wrote a post

Jerry Neumann:about it, Fred Wilson wrote a post about it.

Bryan Cantrill:They do not read her all the way to the end. Do they know that it kind of ends with a guillotine? Exactly, right?

Jerry Neumann:That's what I said. I said, you know, this is weird because what she's saying is that we're all obsolete, right? And I think the job has changed, right? I think a lot of venture capital has become basically front running production capital. It's production capital, but they're doing it private.

Jerry Neumann:And then they're like, okay, we're gonna build this company and sell it to you, right? And a lot of the autonomous driving stuff, right? Like, oh, we're gonna build an autonomous driving company, which we can then sell to a company which needs an autonomous driving company, which is different than taking a bet on technology. I mean, I've certainly made investments, and I try not to do this, but there was one investment I made early on where I'm like, okay, this company might succeed, in which case I'll make a lot of money, or it might fail, in which case I'll sell it to Microsoft and make a little bit of money. Right?

Jerry Neumann:That's not venture capital. Right?

Bryan Cantrill:I mean Interesting.

Jerry Neumann:And and it did in fact fail and we sold them to Microsoft. But you know, it's like, all right, well, why wouldn't I do that? But it's not venture capital.

Bryan Cantrill:And so the I absolutely agree with that. I that that you should really be taking a a bigger swing and not and not and not aiming for the exit. But you think that, like, someone who's putting a $100,000,000 into a company at god only knows what kind of post money. I mean, like, aren't you beyond the window where you can easily be acquired by? I mean, it's like that's a very big acquisition for for a public company certainly.

Jerry Neumann:Well, no. True. I and I I don't think it's production capital in the sense that they're hoping to flip it. I think it's production capital in the sense that they think it's a foregone conclusion that there's going to be one winner here, that there has to be a winner here because it doesn't the bet doesn't make sense as a bet. Right?

Jerry Neumann:And it's true, like, so I'm gonna plug the thing I just wrote, which is actually coming out in the Colossus review this week. And what I wrote about was containerization, shipping containerization, not containers. Shipping containerization back in the nineteen sixties, where there was a ton of money being put into it and it was a new technology, right? I mean, it was an old technology, but the technological system was new and people put a ton of money into it not because they're like, I'm gonna make a, you know, I'm gonna this is a bet that I'm making it risky thing. They're like, well, yeah, this is obvious.

Jerry Neumann:This is obviously going to happen, and I would need to be one of the people who is big in it if I'm gonna make money in it. And that's different. Right? It's it's not saying I believe in this thing. I believe that this could change the world.

Jerry Neumann:It's saying this is the way the world is absolutely going definitely going to have to be. And unless I make a huge bet, I can't be part of that. I don't I'm not looking to make 10 x returns. I'm just looking to make 15% a year. You know, I either if I don't put this $100,000,000 in, I'm not part of that at all.

Jerry Neumann:And and I think that's a different kind of investing.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Interesting. And when because he as you point out in shipping containers, it's it that there's not a a Google or a Fang of shipping containers. I mean, it it shipping containers increased increased global prosperity, but it didn't the the benefits from that did not accrue to a single entity. They were very I I I would say

Jerry Neumann:I will I mean, would there be an IKEA without shipping containers?

Bryan Cantrill:Well, that's what saying. Yeah. Right. Yeah. I mean, that there it's a benefit lots of folks are beneficiaries of it, but it is those benefits were much more evenly distributed than you would have, you know, the the the benefits of, you know, IBM's accounting machines in the twenties and thirties where, like, the benefits of that went to IBM.

Bryan Cantrill:And the you know, they were because even the the punch cards were kind of one time use. Right? So, like, the that was people were were getting the benefits of using this stuff, but it was it was much much less of a much more dispersed, I would say, diffuse for shipping containers. I gotta say, I think like open source is the same way. I I mean, open source is like, indisputably essential for everything that we have built.

Bryan Cantrill:You could not build literally anything today without open source. But the the benefits of that did not accrue to really any I mean, there are entities that benefited from it. Like, you can argue that the Google is to open source what IKEA is to shipping containers in that they were able to build Google because of open source. But they the the the advantages to open source went far beyond Google's walls. Or maybe

Jerry Neumann:she brings

Bryan Cantrill:out the question. Well, like, what what do you make of open source? How does affect it?

Jerry Neumann:I mean, there's two things here. Right? One is, like, who gets who gets to keep the value created from a new technology. Right? And sometimes people can somehow create some sort of moat that lets them keep the value and sometimes you can't.

Jerry Neumann:And sometimes as with open source, they don't even want to, right? So the value then gets spread more widely, but shipping containerization, people wanted to create moats, but there was no moat to create because you couldn't own that. And I think the question with AI is, is there going to be a moat that people can build where the technology won't become more widely available or that anybody can build the technology and thus there's no money to be made, no excess money to be made. Right? And, you know, so this is with shipping containerization, like, there was a frenzy.

Jerry Neumann:People built a lot of ships early on, like they way ahead of demand. There was a bubble in building ships and in investing in building container ships, but there aren't any like, there's no companies you can really point to aside from Sealand, which was the very first company, the one that the guy who really brought open, you know, brought shipping containerization to the world, you know, he started Sealand and he made a bunch of money. He flipped the company. Yeah. But you can't point to like, yeah, you can't point to a big shipping company.

Jerry Neumann:It's like, well, shipping company is because of open source. I mean, sorry, because of shipping containerization.

Bryan Cantrill:No. I think it's but I think it's actually the analogy holds up remarkably well because it's like Red Hat is the company that really made money off of open source. There was an I mean, the in addition to like micro mobility, the scooter, the little VC boomlet, there was an open source VC VC frenzy in like Adam, what was that? Like 2013, 2014? I guess we can just track when in Docker, I think we should track Docker when but it wasn't just Docker.

Bryan Cantrill:Right? It was a bunch of them. I mean, were a bunch of companies that were, and this was when I Ed, I don't know if you invested in any open source companies, Jerry, but the, I remember talking to one VC in particular who would explain to me, well, that's like, no. The reason we're investing is because Docker in particular. They'd invested in the, know, whatever the h round of Docker, and I explained to him that he's gonna lose his money.

Bryan Cantrill:And the the he said, no. No. We're not gonna because the if you look at the adoption of this, the adoption curve is up into the right. And anything like monetizing that kind of adoption is a much easier problem. And I'm like, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:Well, so I mean, just what you said earlier, Jerry, that what kind of investors don't necessarily know what they're investing in. So, like, this is part of what creates the frenzy is they don't actually understand it. I'm like, you're not actually a software engineer and I actually am. And the appeal of a lot of these open source technologies as a software engineer is that I know that procurement never has to be involved ever. Like I never have.

Bryan Cantrill:Like actually, I and so I am attracted to the things that can't be monetized. And you, by looking at the download numbers from NPM on a keynote or what have you, you may actually be investing in those things that are the least monetizable. And there was admittedly the color did drain a little bit. He's like, do you think that's true? I'm like, I think that could be true.

Bryan Cantrill:I don't know. I mean, you're the one that just It's just money. Right. You tell I don't know. You tell me.

Bryan Cantrill:And then and of course, was wiped out. Right? They were all crushed down by the end, you know, I think Benchmark got theirs out of Docker, but it was other a lot of people that lost money on Docker. And but it was not just Docker. There's a whole little VC frenzy around open source kind of very similar to your shipping container example, where it's like, and like, no, only Sealand is gonna make money, only Red Hat's gonna make money on this.

Bryan Cantrill:This is not because this is the benefits of this are more diffuse. They accrue to more people in smaller chunks.

Jerry Neumann:Well, and that's, I think, so to bring it back to something where we don't know what's going to happen yet, because that makes it more interesting, right? Is that true in AI, right? Is OpenAI the only company that's gonna make money? Or is it one of the other ones that have, you know, essentially the same vintage, Right? I mean, everybody else gonna be like, well, okay, you know, we didn't make any money.

Bryan Cantrill:And when you say make money, I mean, didn't OpenAI realize that like they're gonna be spending $87,000,000,000 more than they anticipated? I read that number correctly from like

Jerry Neumann:Yeah. I I thought it was more than 87, but I Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:It's like, wow. That is a so, yeah, maybe by making money. I mean, yeah. Yeah. Our and what do you make of it?

Bryan Cantrill:What do you think? Because I do think it's like I think that we are and I think it sounds like we agree on this that the the even as much as the revolution started in, say, 1971, it has gone through its installation, it's gone through its frenzy, it's gone through its crash, its deployment phase. And we're now in, I think, arguably with AI, we are in the frenzy period of a new revolution. And it sounds like you I disagree. Okay.

Jerry Neumann:Okay. Yeah. So no, I think AI is the maturity phase of the ICT revolution. Also like shipping Shipping containerization was the maturity phase of the previous revolution, right? Because it brought together the technologies that already existed.

Jerry Neumann:I mean, look, AI, what is AI, right? It's computers thinking. Why did we build computers? We built computers to think. So AI is exactly what we asked for.

Jerry Neumann:Right? I mean, that's what it is. Like, people are like, nobody asked for this. I'm like, yes. This is exactly what you asked for.

Jerry Neumann:This is what it does. Right? So, yeah, no, this is the this is the final stage of the computer revolution is computers actually I mean, I actually don't think they think, but, like, you know, this is this is the end game of the computer revolution. That's my that's my opinion. And and and I think No.

Jerry Neumann:I think if it was That's Perez, anyway. It would be different. Right? Like, you'd have so go ahead. Sorry.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Perez agrees with you. I I definitely disagree with you, but Perez, Perez agrees with you. That's what she thinks too. She thinks this is like the the the, you know, that AI yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:That's something she thinks that like the purpose of the ICT revolution was apparently to make, you know, to make chatbots that can rephrase things as like Seinfeld scripts or what have you. That that was the that was the end goal apparently. So That's where we started all along in 1971. Right? That was the ambition.

Bryan Cantrill:That was the ambition. So so what so what do you make? So you do not think we're in a frenzy of a new stage. You think that this is a, this is I more think a

Jerry Neumann:like shipping and generalization. And other late stage technologies. It's, you know, look at every revolution had late stage technologies that were, that changed things like they were big deals, right? They were, you know, increased productivity. And the reason I think, so if this were a new revolution, it would be more like the computer revolution at the beginning, right?

Jerry Neumann:Where you'd have a bunch of people hanging out, you know, in somebody's garage, like talking about this super psyched about it, But most of the world will be like, that's nothing. Like, nobody cares. Right? Because unless it's a surprise, you're not really following the the track of Perez's theory. It's and this Okay.

Bryan Cantrill:But that did happen. So my counter to that is that did happen, that you had the transformer papers written in 2017. You did have people that in in 2017, '18, '19, those kind of years, I remember the a Adam, I I guess that we've had on the show, Mike Cafferrella, I've known Mike for years. I remember Mike, an AI researcher, I remember talking to him in 2019, and he was telling me that, like, language is a solved problem. I'm like, what?

Bryan Cantrill:No. It's not. He's like, no. No. You just don't know it yet.

Bryan Cantrill:But it is based on some of these early results we're seeing, we think it's a solved problem. And he was right. And so I think that that was happening then. And you did have the the transformer architecture very much coming out of production capital from Google. And then kicking off starting with with I mean, with OpenAI.

Bryan Cantrill:I mean, I I it is really hard to argue that we are not in a a financial capital frenzy right now. I mean, is is that is that so ignoring Perez, do you or do you not you believe this is not a financial capital?

Jerry Neumann:I don't believe it is. No. I think it's a production cap.

Bryan Cantrill:Wow. You think it's a production cap. Okay.

Jerry Neumann:And so, I did write this thing ten years ago and my thinking is I believe different than Perez's in a lot of particulars. What I think really kicked off the computer revolution was a bunch of hackers being able to tinker with personal computers without getting permission from anybody, without having to spend a ton of money, right? And because they could do that, they could find uses that big companies wouldn't think of because big companies are gonna look for uses that their customers want. Right? And this is sort of the Christensen disruptive innovation thing.

Jerry Neumann:When companies try to solve their customers' existing problems, they're not doing anything new. Right? So I think if AI was cheap, if you could run it on your laptop, some of these small models you can, right? But if people were running like small models on their laptops, trying to solve problems that only they had, Then you come up with things that nobody else thought of, right? And think that's what made the personal computer revolution so interesting, was people solving problems that nobody was asking to be solved, because then they solved a new problem.

Jerry Neumann:I think it's

Bryan Cantrill:happening today. You don't think that's happening today? I think that this happened today. You don't think it's happening?

Jerry Neumann:Well, I I mean, you Yeah. You there's certain things you're not allowed to do with OpenAI. Right? I mean, you you can't use ChatGP and T in certain ways because they won't let you. Like, there's no permission less invention here.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. But not not with OpenAI specifically, but with other LLMs. And I wonder if there's an an analogy here between,

Adam Leventhal:you know, you talk about some of those early computer hackers. Some of that was enabled by this IC revolution, which was not cheap to achieve. Right? Like, there was tons of money that went into Yeah. To enable that in the same way that there may be there there's clearly tons of money going in to to train these models.

Adam Leventhal:Right? These are not things that people could do in their in their basement with their $100,000,000 worth of GPUs. I wonder if the anyway, I wonder if we're going to see more of what you're describing as that hobbyist phase in the shadow of of maybe that kind of the lithography and IC phase that we saw in computing earlier.

Jerry Neumann:I think that, I mean, I would be surprised if that, the only thing that would prevent that from happening would be if they can't change the technology in a way that makes it cheaper to train, right? I mean, or cheaper to run. I mean, I think that should be possible. But Well, you know, don't think that

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. I mean, the chime for our DeepSeek episode with the streamers folks and like DeepSeek did to that. That that is what DeepSeek did. So, I mean, I I think that where the OpenAI

Jerry Neumann:is still spending a $110,000,000,000 over the next or whatever they said they were spending over the next few years. Like, if it's it's clearly hasn't come down in price, you will

Bryan Cantrill:off to see. So so I think because it's a frenzy. I I I think because it is a financial capital frenzy. That's why. So it would it would be my answer to this.

Bryan Cantrill:Would be that you had I think that that, you know, there are some open questions for everyone about what the the advantage of scale. And right now, I think that this is not my domain, but it is, I think, a reasonable inference that there are people who continue to believe that if we can be that that the only way to own this entire market is to be at the largest scale as fast as possible. And then it's gonna be winner take all. I think that's got to be the the the thinking of folks that are investing in these very large model companies is that, like, it's gonna winner take all. I no.

Bryan Cantrill:I actually yeah. I I I think from it'd be interesting to know their perspective. I think from their perspective, maybe like, hey, you know what? There's a lot of capital being pointed here. And there are a lot of ideas that we have that are not merely improving the models.

Bryan Cantrill:There's a whole bunch of stuff that we can go do it. You know, it it it I throw up my mouth a little bit when I get to KI because I just can proxy Simon Wilson kind of having a heavy sigh when I say this. But I think I the but it just, you know, the the number of things where we are using an LLM and kind of in accordance with some more general purpose compute to just like to do some things, to write some programs to I mean, to to I mean, it's so much better as web search. And I feel that it that is so where the goals are not this kind of we're gonna build this super intelligence, but we're actually gonna use this as a tool. And so I actually see us kind of transitioning us transitioning pretty quickly, and it'd be interesting to know if there's gonna be a crash or not.

Bryan Cantrill:But through this kind of frenzy into what I think is gonna much more of a production capital footing where we are gonna see I and I I I think that there's gonna I mean, I think that the the crash such as it will be I mean, certainly there are a lot of companies that have taken a lot of money that are not these kind of core model companies, I'm sure. Well, I guess you you Jerry, you you have you've retired from the field. And you had a great note, by the way, I gotta say. When you announced your retirement from investing, I really have just like total admiration for that. Do you are you missing it with this?

Bryan Cantrill:Are you

Jerry Neumann:I can't write 100

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Dollar Yeah. Right. Yeah. No.

Bryan Cantrill:I'm not.

Jerry Neumann:I so, you know, I I am technical. That was my first job was I was a hardware designer for my first job. So I I have, I think, generally been better at investing in things that are pretty highly technical, just to sort of a comparative advantage to the other VCs. And so I do miss that part because this is pretty highly technical and I find it super interesting. And I would love to be sitting down with founders and talking about what the next big thing is here.

Jerry Neumann:But I really don't believe that this is a revolution so much as it's an evolution of the existing computing paradigm. Because I don't think people are trying to do different things with it. They're trying to do the same things, but better.

Bryan Cantrill:I, yeah, I don't agree with that. I I think that it's gonna be I think that we don't know where it's I think, like, a lot of these revolutions think, oh, you know, mistake that people make is they think that whenever there's a frenzy and a crash this is like, you know, the Gartner hype cycle thing. Right? If I if you have a frenzy and a crash, then, well, you must be getting to this kind of production capital nirvana on the other side. It's like, no.

Bryan Cantrill:You can be like the lime scooters. You can just toss into Lake Meriden. That's the end. Like, that is actually doesn't need there doesn't need to be kind of a getting on a a more permanent footing. But I think in this case, I think it's really gonna change things pretty deeply.

Bryan Cantrill:I think it's I mean, think it's gonna change education. It has to. It has to fundamentally change education.

Jerry Neumann:Well, it's gonna make peep educators I believe it's gonna make educators more You can't get rid of educators, right? I've Oh no, sure. You still need that person. You still need the doctor, but it's gonna make doctors more productive. But this again, it's shipping containerization, right?

Jerry Neumann:It didn't invent Walmart, didn't invent IKEA, but it made them more productive so that they could become bigger companies and spread their mission globally, you know, much more broadly. And I think that's what's gonna happen here is the value from AI is not gonna accrue to the AI companies. It's going in the end to accrue to doctors and lawyers and educators and people in the knowledge, you know, business.

Bryan Cantrill:So in that, Jared, does that mean that

Adam Leventhal:AI kind of becomes commoditized? That that these hundreds of billions of dollars is kind of a race to to the bottom to some degree. And then these higher value services consume AI, provide, you know, services to their end customers, and that's where the value accrues. Is that is that kind of the idea?

Jerry Neumann:Yeah, I mean commoditized or not, mean, could be that there's only a couple of model companies, it could be it just it's Microsoft and Facebook and, you know, I mean like the Amazon, like running big models and OpenAI is maybe a new entrant there, but I think they're going to compete head to head and you're gonna choose the model that makes sense, or you're gonna be able to run smaller models for cheaper somewhere else. And in the end, you're gonna say, I'm not gonna pay a ton of money for this. I'm going to use it. I you know, I I think it that it is a revolutionary technology. I think that it does things that computers couldn't do before.

Jerry Neumann:I mean, I think it's an amazing technology. I just don't think that value is gonna be captured by these big companies except for maybe one or two.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Okay. So the and this is an important distinction because I think that I can and I can see where you're coming from. The the question is not value creation, it's around value capture. And what you're saying is, this is revolutionary.

Bryan Cantrill:And then this is where it's like the analog beat. No. This is revolutionary the way open source revolutionary. Like, dispute Or

Adam Leventhal:the Internet or the Internet was revolutionary. Right?

Bryan Cantrill:The Internet was revolutionary. Part of that same. Now that but shipping containers had its CLAN and had its IKEA, and open source had its Red Hat and its Google. And so have we're are there gonna be entities like that? That it's not that they're that they are capturing the value creation, but they are benefiting from that value creation to create something wholly de novo that they would not be be otherwise able to do.

Bryan Cantrill:And is that where the the kind of yeah. Interesting. Somebody always makes money. Is this like the investor's mantra that you have in

Jerry Neumann:the, there's gotta be

Bryan Cantrill:You gotta read that to be an investor.

Jerry Neumann:Know, if you read that thing I wrote on venture capital in the 1980s, there was just something really interesting that I learned when writing that, which is that people made money in disc drives, in backing disc drive companies, but they backed so many disc drive companies that the sector as a whole lost money for the investors. So not a good place to invest, right? If if you if you can't pick winners, and I don't think VCs are great at picking winners, they're great at picking sectors that might win, but they're not great at picking like this particular company, except, you know, later in the in the cycle. But you know, if you're a seed stage investor, you can't be like, oh, of the 50 companies that are starting, this one's gonna win, right? Because generally they're started by people who have no idea what they're doing, you know, management wise, right?

Jerry Neumann:You can't be like, these people are gonna be the best managers. You're picking people who have great ideas and hoping that, you know, either there's very few companies or that all the companies win. Like that's how you make money. So I just think in AI, like there's too many companies, there's not enough money to be made. The sector as a whole is gonna lose money.

Jerry Neumann:Somebody's gonna make money. That's true. And they're gonna be like, look, I made money. I'm a genius.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. But

Jerry Neumann:that is that really

Bryan Cantrill:is And I mean, Cisco is still not trading at its 2,000 highs. Right? I think that that's correct. Someone can go look at the but Cisco was I mean, and and Cisco I picked Cisco because it, stayed I mean, basically a healthy company. And so Cisco is, yes, is still trading off of its March 17 to 2,000 high, twenty five years later.

Bryan Cantrill:And Cisco, you know, I mean, really tells you something about that particular frenzy. One thing I I definitely wanted to ask you about, because one of the things that press talks about, I think, is kind of interesting, is that when you have these crashes, they you you get changes, regulatory changes, regime changes, what have you. And it was one of the things that the thoughts I just wanna get, maybe hot take number four, another question for you. The in the dot com bust, one of the things that and then then in the kind of the ensuing, certainly in the financial crash two thousand eight. But the certainly in the dot com bust, we changed some of the and the Enron collapsed, some other things.

Bryan Cantrill:Sarbanes Oxley is in, like, 02/2002. When is Sarbanes Oxley introduced? But we we we things to to make it to make sure that our public companies are more accurately representing themselves. But Silicon Valley views a bunch of these things as onerous and companies stay private longer. I mean, Facebook goes public because they were they had 499 investors and they were out and they that that's a cap that's now been lifted to 3,000, but they literally could not add a new investor.

Bryan Cantrill:They had to go public. What do you kind of make of this trend and how does this kind of affect this of companies staying kind of indefinitely private, not going public?

Jerry Neumann:Well, I mean, first I think, yeah, we definitely had regulation after the crash, but the regulation was so tepid that it didn't made really no difference in Sarbanes Oxley, come on. Like, did that really make any difference? I think the tech sector totally dodged a bullet there. The regulations that could have been put in place were

Bryan Cantrill:farmer owners. Interesting.

Jerry Neumann:I mean, you look back to like, back in the progressive era when they were putting in place like antitrust regulation and actually enforcing it, like that kind of stuff, that made a difference. This, no, this didn't make any difference. Not really, right? I mean, okay, Facebook had to go public. Mean, oh, boo hoo, everybody only became billionaire.

Jerry Neumann:I mean, right? I mean, like, I don't know who's complaining about that? Think

Bryan Cantrill:When they were allowed to go public in a structure that doesn't allow the public to actually own them too, which is the thing that I've I mean, like, how that that I don't understand. That is I genuinely do not understand how I mean, that Zuckerberg can't be fired because of the structure of the company, government structure of the company. It's like, how is that a public company? I mean, how's that?

Jerry Neumann:Same structure, I think. I think still does.

Bryan Cantrill:Is that right? Oh, interesting. Wow.

Jerry Neumann:Anyway, but yeah, no, I mean, I think it's look, you know, nobody in The United States can complain about regulation. I mean, please. Clearly, I mean, it's just, you're getting piggy if you start complaining about regulation here.