Debugger-Driven Development

Was just talking to you with my microphone muted for a little bit, but it wasn't that long.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, one of those. One of those where I'm being like, I'm being ignored. It's like actually although, you know, I had one of those today where I actually I actually hand on heart thought I like, I had a proposal or something in a meeting and everyone's everyone's driving on I'm like oh I was muted. I went back and like I actually wasn't muted. Actually everyone heard me and really thought my idea was my idea was a stinker.

Adam Leventhal:We just wished we hadn't. Yes.

Bryan Cantrill:Exactly. He's

Adam Leventhal:Oh, sorry. I was mute. Oh, nope.

Bryan Cantrill:I was not muted. No. Never mind. Oh, god. It's happening.

Bryan Cantrill:I'm not muted right now. Delightful. Alright. We gotta I are you yeah. You gotta we gotta bring it up.

Bryan Cantrill:Let's bring

Adam Leventhal:it We don't have to. They can just help themselves up. I know that, Brian, you feel like you need to be invited or invite yourself up.

Bryan Cantrill:No. I do invite myself. Don't I invite myself? I I I but I have to, like, raise my hand to get up on stage, and I feel that they Sure. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Know your your hand's shaming me again. Yes. Like we've hey, are Tomax's name on here? Because I don't see them or do I? I do see them.

Bryan Cantrill:There they are.

Adam Leventhal:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Craig and G R. Yeah.

Adam Leventhal:They're doing their thing.

Bryan Cantrill:They're they're doing the thing. Alright. Wait. They were you know, I'm sorry. I was listening to our episode from last week, which is great with Steve Yes.

Bryan Cantrill:Gavnek. And you had told me that you had done some auto editing that you were particularly proud of. And you you felt like I I I don't feel that I am exaggerating when I say that this is this is some really strong work. Well And Yeah. And you mean

Adam Leventhal:I told you that? You're like, because I I think I I think my words were like, I'm not overselling it. This is the best thing I've ever done in my life.

Bryan Cantrill:And I I just I emphatically agree. I when it actually when I hit it, I was I just burst out laughing. I really was laughing out loud. It was very, very fun.

Adam Leventhal:Good. Well, the other thing I really enjoyed was the visual Easter egg in the YouTube video, which did cause me to, like, miss a a significant fuck up in the audio.

Bryan Cantrill:But but in terms

Adam Leventhal:of I have no regrets.

Bryan Cantrill:If you if you undersold the the JJ horn, I feel that that one I mean, we're not gonna use the word oversold, but I Okay. I love that. Yeah. So that and then I also loved that we had the the chime. We had the the chime that we use whenever we reference a previous Oxide and Friends episode.

Bryan Cantrill:I love the fact that our chime, it is not actually like a happy sound that like the the Mac SE would use when it boots for example.

Adam Leventhal:No. It is it is the boot sound. It's the happy boot sound. I just took you on long error sound.

Bryan Cantrill:Isn't it like there's no boot device found?

Adam Leventhal:No. I took you on a long walk that that that was confusing when I introduced that sound. But no. It is the it is the happy, like, MacBook has survived post. Yes.

Bryan Cantrill:I thought that was like we have not survived post. It's got a bit of an angry undercurrent to it. I I thought it it's got a little bit of a what I liked. I kinda like the fact that's like a it it it it that fight or flight reaction that it is. Anyway, we you were ringing the chime actually quite a few times in the the previous episode previous episode.

Bryan Cantrill:But then when I actually prompted you to ring for the chime, you did not ring the chime. And people were wondering, is this like passive aggressive? And my view is like and I think it's actually the truth is just like, dude, you wanna try auto audio editing this thing? This is not this is a lot of work. This is like I'm actually very busy with this visual gag at the end of this thing that is way more important than anything else right now is that we are slowly panning the image to me on my phone, manipulating it while I guess it was at the meta kind of point of that?

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Yeah. Okay.

Adam Leventhal:But but no, it was aggressive, actually.

Bryan Cantrill:It was actually wasn't it me?

Adam Leventhal:No. No.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, go go go. Yeah. No. It wasn't. Was

Bryan Cantrill:it I mean, I kinda

Adam Leventhal:wouldn't But I would say that you and nobody else on Mastodon enjoyed it. Everyone on Mastodon was very clear that they don't like the chimes. And to the folks on Mastodon, I say, I'm sorry you don't enjoy them, but

Bryan Cantrill:I was just enjoying them, but the the the chimes are staggering. We love we I I love the chimes. And I and I also kind of love the fact that like it's like nirvana. You can't seek it. You can't ask for the time.

Bryan Cantrill:The time occurs because you've made a natural reference to a previous episode. You can't call for it, which I can all I can also like. So Exactly. I think was really the audio editing was really absolute top notch. The visual editing, pretty good.

Bryan Cantrill:Pretty good. And I I I I can also see like reasons why I can see why that would be important to you and that you'd proud of it. So that was pretty good. It was I did was pretty good, honestly. I'm I'm being it it was it was better than pretty good.

Bryan Cantrill:I I did enjoy it. Well, I feel like Slow pan into it and out of it. I thought

Adam Leventhal:that Well, like an an audio I mean, a visual gag on a YouTube video that you have surely backgrounded and also plays out over the span of twenty five minutes is, you know, arguably a little bit subtle.

Bryan Cantrill:You definitely you know, I'm sorry that I was not wearing a helmet cam when I was actually watching that because you would have been I had much more satisfaction because I was in the grocery store like shopping as I'm listening to it. And so I'm like, you know, I I'm like

Adam Leventhal:Adam told me there's a visual gag. I better get my

Bryan Cantrill:The visual gag, get the peanut butter, it looks like one thing, and then I'm over to getting like the butter and it looks like something else. I'm like, wait, what what did that happen? So it was like, you know, it would it would have given you much more satisfaction to like me retracing my steps and, you know, somewhere between the peanut butter and the butter actually.

Adam Leventhal:You're welcome.

Bryan Cantrill:Good stuff. It was good stuff and I I really it was a fun episode. That was a a fun conversation received. No fun that they actually had a another follow-up conversation on Matthew's podcast. So it's kinda weird.

Adam Leventhal:Yeah. And like some other lesser podcast as well.

Bryan Cantrill:It's it's Well, clearly. Yeah.

Adam Leventhal:If and I mean, lesser lesser than Matthew's. I mean Right. Yeah. Apparently, it's really put him on the the podcast circuit.

Bryan Cantrill:There there you go. Well, I

Adam Leventhal:was So to our guest tonight.

Bryan Cantrill:Yes. And and speaking of the podcast circuit, I am I am so excited about this topic. I was convinced we've already hit on exactly this. So we are are are are talking about debugger driven development. And this is prompted in part because we talked about our dev the demo Fridays that we do.

Bryan Cantrill:And we had a demo Friday on last Friday, which was great. And all three of these cats here, Dave, Eliza, John had demos that were had at their epicenter a debugger and to to demo kind of other things. So I wanna kinda get into that because it it did remind me like, man, we this is this is such a great topic. And, Adam, I think he I don't think we've talked about OMDB at all. David, we have we even mentioned OMDB?

Bryan Cantrill:I think we probably mentioned OMDB in the sagas episode. I think we must have hit on it at least a little bit, but I'm not sure you That's a question.

Dave Pacheco:I don't remember.

Bryan Cantrill:But we and you know that that the Dave, think the last time we had you on was like nine months ago, which is kind of amazing.

Dave Pacheco:Was that the sagas one?

Bryan Cantrill:The saga yeah. I think the sagas one was like Yeah. In August, I think.

Dave Pacheco:Which is Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Kinda crazy. Again, sorry to Jim. But I well, obviously, a lies on that one as well. The but I wanna actually maybe if we can rewind. So what we did talk about Adam and and you were referring me to our with what is a bug?

Bryan Cantrill:What is a debugger? Right. Back from the that that was like

Adam Leventhal:02/2021. Right? That was like an early Twitter space. Early.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Did you listen to it? No. It is early in all of the ways. Let me just say that.

Adam Leventhal:Little rough.

Bryan Cantrill:At some point, I accidentally mute you, and I can't I'm like, Adam what happened to you? Like where are you? Adam. It's like is Adam there? What's going on with Adam?

Bryan Cantrill:Adam is gone. And then like I have muted Adam. So anyway it was there was a there a whole bunch of just Also

Adam Leventhal:shows the evolution of editing because apparently we just left that in too.

Bryan Cantrill:And we we just left all that in. Yeah. That that garbage is now living forever. But we which it was an interesting discussion, but it was really not hitting exactly the topic that we wanna hit today, which is really using a debugger not merely to debug a system, but as part of developing that system.

Dave Pacheco:And, you know, I was

Bryan Cantrill:kinda thinking back to mean, Davey, you as as I was kind of approaching you about the about the possibility of taking on the topic. You asked me what I'm not sure if it was like a rhetorical question or like a test of proof of life, but you did ask me like, do you mind if we start with like a historical perspective? I'm like, is this are you making fun of

Bryan Cantrill:me right now?

Bryan Cantrill:I mean, like, we're obviously gonna start with this. Right? Right? I mean, it's not.

Dave Pacheco:I did. I was wondering if that was a silly question.

Bryan Cantrill:It's definitely like I mean, it's I mean, for sure. I mean, again, I'm not sure if it's a trick question or not. But so actually, do you wanna kick us off a little bit and maybe hit on that historical perspective? I'll obviously I I think, you know, we've obviously got our own historical perspectives as well. But

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. So, I mean, I don't know how far to go and, like, how much to dive into some of this stuff. I mean, for me, there's a there's a clear line here starting with MDB and Yeah. Going through a whole bunch of different tools at Joint. And but but I think definitely starting with MDB makes sense.

Dave Pacheco:And so for me anyway but I mean, by the time I started my career, MDB already existed. It was new to me. Right? But it already existed. And MDB was the is the Solaris and the Lumos debugger.

Dave Pacheco:Right? What what release was it introduced in?

Bryan Cantrill:Source seven.

Dave Pacheco:Solar seven. Yeah. I feel very, silly talking about MDB history because I I wasn't there and you were, and I'm like, what? I'm gonna get all of this wrong. For for me so so for folks that don't know, MDB is the debugger introduced in Solaris seven, and it is a lot of people, when they hear the word debugger, I think, think of a very specific thing, which is something that can attach to, like, a process or a kernel and can control execution of that thing and print out, like, very low level state, like, maybe, global variables, stack information, and stuff like that.

Dave Pacheco:Right? And that is definitely in the realm of what MDB does. But what makes it different from most of the other debuggers like that that I've used, certainly at the time, is that it provides much richer support for adding your own commands for interpreting the in memory structures. So, like, if you're debugging the kernel, you can do things like walk process, walk proc, which walks over all the processes. And it's an iterator that just, like, enumerates all of them.

Dave Pacheco:And then you can print the proc t, but you can also do something like, p s, which is a a d command that like, the p s command prints out basic information about that. And you can use this to do, like, pretty sophisticated things. So you can walk process walk processes and then pipe that to walk. Red, I don't actually remember. We have to do that if you're piping it then to stacks.

Dave Pacheco:And stacks is this I think it's just a great, example because stacks takes a whole bunch of threads on input, or is it thread stacks? I don't remember which. And, groups them, essentially, creates a histogram of the unique stack traces and also provides filters and stuff. So you for example, if I'm on a system where I think the IO is hung, I might open up MDB and do stacks dash m ZFS, and that shows me all the stacks from ZFS, and it's like a frequency count of all of them. And very often, you're looking for, like, either the thing where there's a zillion stacks or the thing where there's only one stack and it's different from all the others.

Dave Pacheco:It's often like one or the other. But the point is really that it's providing all these much higher level tools for summarizing the state and also diving into individual pieces of state. Right? This is for me, this is, like, actually the bigger takeaway from MDB. I used that part of MDB like, I I'd say 90% of my use of MDB was either on a core file or a stopped process or a kernel that was live, but not like, the fact that it was changing was not relevant.

Dave Pacheco:I wasn't trying to control execution or anything. I was just trying to get date out of this thing.

Adam Leventhal:And part of your point, Dave, I think is that what you can do is application specific. Right? There there were these modules and commands that were customized for the kernel for even subcomponents of the kernel, not just, like, read and write bytes, which it could also do, but there was this much richer interface that could be extremely application specific.

Bryan Cantrill:Totally. And you and in particular, the modules themselves were written in the same language as the system, namely c. So you could there's a class module API, and you can write this dynamic module that can then be loaded in. And it it's got the the ability we've got a bunch of class notions in there that were useful for writing debugging commands. So the idea you mentioned today, the idea of of walkers, which is our way of it it one of the things we noticed, like, we're constantly iterating over things.

Bryan Cantrill:And you wanna have the intelligence over how to iterate over something and separate that that out from the intelligence that knows how to do something with that thing. And that's you know, a lot of that came from actually I mean, we were using MDB to actually debug Solar seven. So Mike the history here is that Mike and I were the gatekeepers for Solar seven. And we're the the and we were debugging it fell to us to debug all these different problems. And I actually had developed something called dump information, DI, d I, that do you remember this?

Bryan Cantrill:Never knew about DI. Yeah. And the and we really wanted to do something much more class. And so, Mike, when he started at Sun, one of the things he did was actually improve the Solaris two six boot time, which resulted in the invention of the p grab command, which has since been ported to many other systems. But p grab has its origins there in that work.

Bryan Cantrill:And and then immediately after that, we started work on MDB, which stands for the module debugger, putatively. We all know it actually stands for Mike's debugger. And MDB by having this idea that modules were written in that you could write them in c with a really class API, you could do really, really rich rich debugging support originally for the kernel, but then also extended up into user land and kind of seeing what things that folks had done with crash, which is a crash is a an SVR for utility that was much more powerful we felt than than ADB, but then also had a bunch of limitations. So that was the the rationale for it. And then some of those the the early things that we developed turned out to be like, wow, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:This is really clearly the right model. So we, you know, had the ability to walk every KMM cache. And then for every KMM cache, you could walk all the memory that have been allocated there. And then you could paste those things together to do colon colon what is, which allows you to take an address and ask what is this thing? And it would tell you everything it knows about that thing.

Bryan Cantrill:And we were putting that together with some of the bugging support we had in the allocator. We were able to do some really, really powerful things.

Adam Leventhal:Dave, this might sound quaint, but I'll I'll tell you what blew my mind when I joined the Solaris Kernel Group was I I think that we had just gotten type information into the Kernel and therefore into the debugger. So

Bryan Cantrill:Yes. That's

Adam Leventhal:right. Extremely exciting. But the colon colon list command that let you say, like, okay. Here's an address, and then here's how you get to the next item in a linked list to then iterate over them. I've like, that was just just mind boggling.

Adam Leventhal:I know this sounds incredibly facile now, and we've built so much on top of that. But but without that, you're sitting there, kind of hand iterating through everything. It was it was a it was amazing in the moment.

Bryan Cantrill:Absolutely. And then as think Jason's saying this in the chat that you could but by having pipelines, it's a class idea. You got all that power of Unix where you could actually string, you know, your con con list d command together with a bunch of you could have these very complicated invocations that allowed you to really run the the really sophisticated queries of the state of the system. And really, I I think extraordinary valuable stuff. So by the time, Dave, you joined us in 02/2008, MDB was definitely well established, I think.

Bryan Cantrill:We'd For

Dave Pacheco:sure. Yeah. We started We had a bunch of d commands and stuff for AKD already at that point. It's the the application we were working on at the time.

Bryan Cantrill:That's right. Yeah. Yeah. Right. Right.

Bryan Cantrill:Right. Yeah. I've I've forgotten. Because we we did a bunch of of AKD was the appliance get daemon that we developed at FISH Works, and we had done a bunch of of MDB support for it. I'd forgotten that.

Bryan Cantrill:Alright. So, Dave, so MDB and I actually as I was kinda reflecting on my own history of if you'll forgive me, slight tangent on this, the of my own history of of debugger driven development when I was developing the Cyclix subsystem, which is how we do high resolution timers in the operating system, and replaced the the the traditional interval timer that we use for the system clock, The Cyclics facility, I very much code like, MDB existed before that. Right? I thought I introduced that facility in Solaris eight. We already introduced MDB in Solaris seven.

Bryan Cantrill:And so the the d commands that that I used for Cyclex, I developed very much in concert with Cyclex, and I used the those d I've I've many of those d commands, I'm convinced. I am the only one in human history that has run a bunch of those d commands, but they were extremely valuable for validating my internal state on something that was still in development, which I think it the I I we for the that that's that's part of what I think our theme is today because I think what you all done is really taking that to to much grander levels. But that idea that, like, as you develop the system, you're developing the debugger support, and the debugger support is then helping you in the the it's accelerating you in developing the underlying system. Certainly true for me in Cyclics.

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. Definitely. Yeah. That that's really interesting. That that I know exactly that feeling you mean.

Dave Pacheco:I I love I have these commands as well, and and some other stuff as well that I'm like, I think I'm the only person that's ever run this, but it was so critical.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. So do you wanna fast forward to kind of Joiant days and some of your use of of m d b there and kind of your your expanded thinking of this?

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. So, in 2010, I left Sun and went to Joyent to work with Brian on cloud analytics, which I think it's fair to say the the very short version of that is kind of distributed DTrace with that was the vision, which was that you could, make some API request to a public API for this cloud and start having that run a bunch of Descripts on your application that was distributed on a bunch of nodes in the cloud. And I you know, obviously, we had to debug that thing. So it was a microservices thing. It had these instrumenters running on each of the nodes, and it had an aggregator service that was aggregating all the data and a config service that was taking all the requests and figuring out what to do.

Dave Pacheco:And you could, at least in principle, run into all these problems where, like, this one node isn't instrumenting something it should be. Let's go wanna look at the state of that node, or maybe you wanna look at the state of the aggregator or whatever. And so we have this tool for doing that. It was a very ad hoc tool for basically querying each of these things. And it's pretty different from MDB in that it's it's use it's it involves the cooperation of the thing that you're trying to debug, and that is a pretty big difference

Bryan Cantrill:that Yeah. Okay. Elaborate on that a little bit because I think yeah. That's actually Elaborate on that.

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. So MDB on the kernel actually, MDB in general. On the kernel and when you're attaching it to process or using it on a core file, the thing itself that you're debugging, whether it's the kernel or the process or it's a dead process in the case of a core file, is not really helping at all. All the logic for figuring out, like, what to show you, how to interpret these things, how to walk these data structures exist in the debugger, and it's reading stuff out of memory or out of the image in the core file and, like, processing that in the debugger, which is very different than, for example, what this thing was doing is making an h t actually, was an AMQP message, but AMQP or HTTP request

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, the eyes starts twitching. Yes. Yep. Sorry. Go on.

Dave Pacheco:Not all the best choices, I think, but but a choice we made. But you're making a request to that thing, and it is answering that request with some information. And that very much limits the kinds of things you can do potentially. Like, you can't like, for example, in the AMQP case, if the problem was that it's not draining its message queues fast enough or it's not connected to the AMQP broker or something like that, well, you're not really gonna be able to debug that with this. But there are a lot of other types of things that you can debug.

Dave Pacheco:What for for failures that are not fatal and not pathological in that way, it's still very useful. And it's kind of important because, again, we're doing this on a cloud where we might you might be instrumenting, like, dozens of systems at the time, which felt like a lot. And it's not you can't, like, attach a debugger to all these systems and inspect the state on each of these things. Right? Some way of automating that part of it and the collecting of information and it's I guess we could have tried to automate that using some in memory thing, but at the time, we definitely didn't have any way to read state out of the node process.

Dave Pacheco:We ended up building that later, which I wasn't actually gonna talk about, but but, but, anyway, that that would have been a harder path, I think. Yeah. But at some point, I I what I was realizing was that this was kind of a general problem. Namely we have a bunch of we have some services with a bunch of objects. In this case, they were instrumentations.

Dave Pacheco:And the services had different views on some of the same objects. Like, a user might create an instrumentation, and there might be 10 instrumenters that have their own view of basically what their view of the instrumentation is, what am I supposed to what descript am I supposed to be running? The aggregator has a view, which is, like, what data do I have? How am I supposed to be aggregating it? What frequency am I how long am I supposed to keep the data and stuff like that?

Dave Pacheco:And we wanted to create a sort of combined view, but none of that problem was really specific to the application. Those are just they're just objects. Right? And so I tried to generalize that into a a component that I basically feel like never got enough love, I mean, for me, which which I called Kang because I had the image of Kang and Kodos in

Bryan Cantrill:the spaceship Yeah.

Dave Pacheco:A little bit being, like, foolish earthlings, totally unprepared for the effects of, you know, whatever this thing is. And so Kang but Kang was this really simple thing. It it you know, these were node programs, and it was a little inch TTP endpoint. It would be the exact same endpoint in every process. And the the endpoints were list the types of objects that you know about, and it would just be an array that's like the string instrumentation.

Dave Pacheco:And then list all the instances you know about, which would be, like, a bunch of IDs, and then fetch, like, information about those instances. And then the CLI for this thing, you would point it with a bunch of, like, IP port pairs at a bunch of these things, and it would go collect what it called a snapshot and assemble, like it wasn't atomic, but a coherent summary of all of the objects from all of the parts of the system that that you pointed it at. And, this ended up being we never ended up doing this for cloud analytics, I don't think, But we did use this in Marlin, which is the compute, the compute component of Manta, which we did at joint. Right. It's like a it's a s three like object store with compute built in.

Dave Pacheco:So the compute part of this would be that you could submit a thing that's like, I wanna run grep on my 10,000 log files. And those are distributed across, like, a couple of dozen or a couple of 100 servers, and we're gonna basically go run grep on all those servers and collect the output and make it available to you. And so this is totally a case where you've got job supervisors and you've got the things running the jobs, and they all know about jobs and they all know about tasks. And they know about other things too. Like, the job runners had this idea of zones, which were the containers we were running these things in, and we needed to know about the state of all those things.

Dave Pacheco:And so all of this, we basically it was incredibly dumb and simple, but basically it would return just a summary of all these objects. But we were able to put together this dashboard that was incredibly useful. I have a screenshot here. I don't know if it's useful to can I, like, dump that in the chat?

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Yeah. Definitely.

Dave Pacheco:Is that, like, useful?

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. We we we've now granted the rights to drop images in the chat. I've been we've some permissions problems. Discord has not been without its Twitter spaces like challenges. But, yes, you can.

Dave Pacheco:Did that show up? Yeah. So that what you're looking at there, I redacted just, like, some some, like, host names and stuff like that. This UI is very specific to the application, but the underlying transport is not. This thing basically just it was a paying client that knew how to go ask all these things, what objects do you know about, and then it would know, like I said, it would assemble the snapshot.

Dave Pacheco:And from this, we got this dashboard. In this case, like, we I spend many hours looking at this. It's bringing back a lot of memories, not most of them not that great, but

Adam Leventhal:the the

Dave Pacheco:black boxes here are containers essentially that are running user jobs, and the white ones are containers that are available to run some users' jobs. And so we would use this to go whether it was an outage or if we just wanna see what was going on in the system or how subscribed it was, we could go look at this and get a really quick summary of what was going on for this distributed system. And and the reason I bring this up is the vision for this was definitely MDB for a distributed system. That's like

Bryan Cantrill:But 100% what I was trying

Dave Pacheco:to go for.

Bryan Cantrill:I have not thought about this image in a long time, and you've just bought back a flood of memories. Because I mean, it's been damn near a decade since we've really I mean, not quite a decade, but it's been a long time since since we looked at this thing. Yeah. And, right, this was this was invaluable. This was so essential at the time.

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. It was huge. I'm just looking at chat.

Dave Pacheco:There's there's a bunch of good questions about this I'll have to come back to. The the disabled one is interesting. So what conditions result in disabled? Unspecified brokenness would result in some of these containers becoming disabled. And it was very helpful to get this at a glance view of, like, how many of these did we have and where were they?

Dave Pacheco:And I think they're if you click through to some of the other tabs there, you could get, like, the error message or something like that. Those are basically, like, problems that we didn't expect to have happen, and we wanted to know about them and dig into them. Yeah. So the I really do view that as, kind of a middle a middle step here.

Bryan Cantrill:A middle step here. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Right.

Bryan Cantrill:No. It's it's like I completely forgotten about old Kang, And I'm I'm sorry. I'm sorry, Kang. But you're right. This it really is a middle ground between it it it was incredibly valuable at the time.

Bryan Cantrill:So yeah. Interesting.

Dave Pacheco:So I guess fast forwarding to oxide, I was going back to the history of this and I was shocked at how recent

Bryan Cantrill:It's very recent. It actually is. Yeah. It's very recent. For something that it's yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:It's it's an idea whose time that clearly come. Yeah. Oh, okay. When is it? I almost wanna write down a piece of paper and flip it over.

Bryan Cantrill:But I am gonna say, I think that that it's gonna be like I'm gonna say like February 2023. Am I still way far off?

Dave Pacheco:Not way far off, but it is later than that. It is after we shipped our racks.

Bryan Cantrill:You know, I should have thought right. Right. So it it was like August, September?

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. September. It was September 2023. And I'm surprised too because for me, the motivation for OMDB specifically was a project I worked on and I I had to have done that before we shipped the racks. So I'm surprised that to discover that this didn't land until after that.

Dave Pacheco:Right. I'm not sure what happened with that. But I remember

Adam Leventhal:I mean, Dave, you were you were very reticent about writing it, I think, is is what happened. Is you're like, I think I should write this thing. Should I write this thing? I I think the same thing that happens for a lot of us, for a lot of tools, which is I think we need this tool for this thing I'm working on. But maybe I should just work on the thing I'm working on.

Adam Leventhal:And then and then after you've done that, you're like, I really wish I had the tool.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. I I think also if you're calling up Adam and and asking if you should write it, I mean, I guess it's like one step shorter than calling me up, but it's definitely a you're definitely not dialing for no when you're up with it. Yeah.

Dave Pacheco:I did not remember that. Wow. So I mean, part of it I think is that there there just wasn't a thing here. So, like, I mean, I don't know if gonna talk about this, but, like, it quickly became a place that you could just put a whole bunch of things that didn't I don't know how to describe it. Like, they didn't have to be super coherent.

Dave Pacheco:I mean, I guess we should describe what it is this

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Yeah. Describe what ODB is. Yeah. Exactly.

Bryan Cantrill:Read the tweet.

Dave Pacheco:So m oDB is it is a program. It is not a debugger in the sense of a thing that controls execution. It's more of a debugger in the kang sense. It's a thing that has a bunch of commands that go make requests to a cooperating component to fetch state about that component, and in some cases modify it. It can control some things as well.

Dave Pacheco:And then summarize that for you. So it's intended mainly for people, although you can do some automation stuff with it. I mean, it has some facilities for that. And it its top level commands all correspond one to one with components of our system. So, you know, there's a DB command, which you point at our cockroach DB database and is a cockroach client.

Dave Pacheco:It's not it doesn't go through any other component. It talks straight to the database. And it has a bunch of sub commands for summarizing state out of the database. There's another command for Nexus, which is our main control plane component, and it makes requests to the internal Nexus HTTP API to, again, fetch state about that thing. And, similarly for other components, our storage component crucible and sled agent and a bunch of stuff.

Dave Pacheco:That's basically what it is. And on some level, like, that's all it is, and, like, that's not that interesting, I guess. But I think what's interesting is the process around it and the sort of, like, flow that it enables. That's been really good. So what I was getting at was, like, there's not like, if I wanted to have a way to get information about Nexus before o m d b, there just, like, wasn't really a place to put that thing.

Dave Pacheco:You create an an API, which is something that's how it started. Like, you can create an internal API for it and you could, like, hit it with curl or you could make a custom CLI. This is basically how it started, but it was just there was just enough vision to be like, this probably won't be the only time we're gonna do this. But once it was there and there was a skeleton for it, I think people really went to the races in terms of, like, lots of stuff got added with the ability to talk to a lot more components, the ability to fetch a lot more state and summarize that state, dive into that state. And that has been just incredibly valuable on so many levels.

Bryan Cantrill:And so, Dave, it was my memory that you demoed this, and everyone is like, where has this thing been our whole lives? And, I mean, it was just one of those things that, like, again, was an idea that had clearly come. And as you say, it's like, on the one hand, it's like, yes, you can do a custom COI, and maybe you can view this as just like an extensible thing. But it just like the way you did it invited other people to participate. I think this was the strength, actually, original strength of MDB as well.

Bryan Cantrill:The that module interface invited people to participate and to do like, hey, you don't have to worry about the whole thing. Just write your logic. You don't have to worry about the COI wrapper and all the other kind of GUCs. You can just write the thing that is actually prints out state about your thing, and now you've got a way of getting it. And I wanna I wanna say that it was like the next week that you had some OMDB based functionality to demo.

Bryan Cantrill:Am I remembering that correctly? It was very, shortly thereafter that other people were demoing OMDB based functionality.

Alan Hanson:I I know it was too, but, I mean, what what Dave did was he he gave us all, like, a taste of crack. And it was like, look at this little it was so it was so addictive. Sorry. To create these little programs that could just give you this insight into what was going on.

John Gallagher:But you can see this if you look at the PR history. You just search for OMVB and look at the closed PRs, and you look like Dave landed this on September 14. And within a week, like, Ben added stuff for Oximeter, and Sean added stuff for SLED agent, and Alan added stuff for Crucible. Like, all this stuff landed. It was it was like, nobody knew this thing exist like, this thing hadn't existed.

John Gallagher:And then it showed up. And literally within, you know, seventy two hours, was like, oh, yeah. I need to put my thing here too.

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. I remember one of the one of the things we did, like, probably right after the demo, we were like, well, we should have some, like I don't know if I don't know if we were, like, we should have some ground rules or what, but it would we needed, like, a little bit of, like, can I just, like, dump stuff in here? I do think there were people that came and were just, like, can I just, like, add something to this or whatever? And I added a block comment that was like the ground rules for OMDB, which you're probably linked to. The one Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:I'm not sure. I'm not sure. I think I've I've contributed to OMDB. I don't think I've read the ground rules yet. I was I was is there no running on the deck?

Bryan Cantrill:Am I not supposed to do I have to shower before getting into the pool because No.

Dave Pacheco:No. No. It's it's very much the opposite. I mean, for the most part. So the rule Okay.

Dave Pacheco:Is like there's there's not a

John Gallagher:lot of ground rules.

Bryan Cantrill:It's basically I've been running on the deck all the entire time. That's great. Okay. Good.

Dave Pacheco:It's it's it's explicitly because I because I think this did come up because people were like a little bit reluctant to be like, can I just like dump some random stuff in here that would be useful to me? And I was like, please do that. So the thing is, like, if you feel if there's something here that is useful, you should add it. I think there's there's a thing about safety in there, and we can talk about safety a little bit later. Like, it's a little bit you don't wanna have something that's, like, if someone runs this command with dash dash help and you, like, aren't parsing that argument and it just goes and, like, you know, shoots Nexus and or something like that.

Dave Pacheco:You don't wanna have people accidentally doing bad things to systems. But but certainly read only stuff that's not gonna be disruptive, like, yeah, definitely put it in there. And then we built some some facilities later for making it so that it would be harder to accidentally run destructive things. The ground rule that I thought was pretty important and is not a surprise to anybody here is, debuggers should never lie. And so here.

Dave Pacheco:I'm gonna I gotta find a link to this block comment.

Bryan Cantrill:Debuggers yeah. Debuggers should never you know, it's funny because we actually talked about this in that that episode from years ago. And and I I'd phrase it if debuggers should only lie if they have to choose between lie and killing the patient. But I was just looking at myself. I'm like, what kind of a choice is like, what condition do you have to lie or kill the patient?

Bryan Cantrill:Is that a choice that a debugger off? What kind

Adam Leventhal:of trolley problem is this? Right?

Dave Pacheco:Like, the poll

Bryan Cantrill:debugger trolley problem. It's like, I go no. I actually question the premise. Like, surely there's a option where we could decelerate the trolley without actually killing anybody. So I I yes.

Bryan Cantrill:Don't kill the patient. Also, don't lie. You can do both. Hold yourself to a higher standard.

Dave Pacheco:And it it sounds obvious when you just say it. Right? But the the example in the comment is like, we think of things like the list of instances on a sled as like a well defined thing. And in a working system, that is a well defined thing. But there are many different things you might mean by that.

Dave Pacheco:There's the list of propolis processes. There's the list of things that sled agent is tracking. There's the list of things that nexus is tracking that are running on a sled. And in a broken system, any of these might be different. And so the advice here, such as it is, was basically like be precise about what you're saying.

Dave Pacheco:You know, don't say this is all the I mean, that one's just vague potentially, but, like, you don't wanna confuse someone into thinking that it you're they're looking at something that they're not. And so if anything, it's probably overly pedantic because a lot of the stuff I write winds up being kind of overly pedantic about this, but in the name of really trying not to lie. And then there there was a one that got added later that was just basically, like, pry hard to keep going even when things aren't quite what you expect. So as an example of that one, the d b subcommand talks to the database, and it uses our regular, library for doing that, which the thing it does is check whether the database schema matches what it expects it to be based on what version of the software it was built for. And if it doesn't, our production stuff just, like, bails out because, like, something horrible has happened.

Dave Pacheco:But the debugger tries. It's, like, it prints out a message. It's, hey, this isn't quite what I think, but I'm just gonna run anyway. I just wanna let you know that this might might be wrong, but it might also be exactly what you need right now. I don't wanna Yeah.

Dave Pacheco:Not give you information because I'm not sure it's right.

Bryan Cantrill:So and this is where you do get into the the kind of the MDB zeitgeist of not having total system cooperation when you're debugging it. So with this is where we may have a system that itself is pathological. So things may be unexpected in the system and we still want to try to drag ourselves along and do the best that we can. Right. I thought that was there

Alan Hanson:from the beginning, Dave.

Dave Pacheco:That oh, that rule? That rule?

Alan Hanson:Yeah. It was I remember you you I remember you explained to me, like because we're things are messed up and we're trying to figure out what's happening. Do the best you can at not blowing up.

Bryan Cantrill:Alan, are you just rude to emphasize the fact that you have read the ground rules and the rest of us haven't? I feel like this is this feels unnecessarily sharp. I mean, I just feel like this is pointed. I don't know. Maybe I'm I'm overly personalizing it, but

Dave Pacheco:I don't know.

Alan Hanson:I found you.

Bryan Cantrill:The so but the it's other thing I think is interesting, Dave, is like this so this OMDB has been hugely helpful for us. And this is as, as Andrew on Blue Sky pointed out, that the I'd asking that or actually, excuse me, asserting that Oxide is secretly a cult dedicated to producing as many new debuggers as possible. That we are which is not true because we're actually I I don't know how that can square with us being a podcasting company. Or maybe that's what it is. We're secretly a cult dedicated to producing as many new debuggers as possible for purposes of content generation, which is I I I I buy that.

Adam Leventhal:Sounds right.

Bryan Cantrill:That's right. The because I mean I mean, this is not the debugger we've created at oxide, and Humility has also been has got some similar zeitgeist, but I don't think you've used Humility that much, Dave. Is that

Dave Pacheco:I mean,

Bryan Cantrill:I think you've I don't think you this is actually OMDB is coming much more out of the the kind of common engineering approach we have across the company rather than direct inspiration, I think, humility. I think he's much more inspired by MDB than humility.

Dave Pacheco:I think that's right. Yeah. But I mean, there's obviously common threads there. I mean, common ancestry there. Right?

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. For sure. They're they're cousins.

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. Right.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. And not by marriage. They're they're they're blood cousins, humility and all MDB. But humility has also been really important for us as we have developed hubris. We have it's similar I I just reading your ground rules for yes, the time along that.

Bryan Cantrill:Although I do love the fact that the the the ground rules, that there aren't a lot of ground rules makes me feel a lot better about not having read them. But it is similar kind of like because you're trying to give people the the permission and the flexibility to develop debugging infrastructure quickly. That's I'd be I feel that's kind of the the the meta point of that. Is that is that a fair read?

Dave Pacheco:That's exactly right. Yeah. I mean, the the rules such as they are, we're actually supposed that's like an invitation. Like, here's the balance. It's pretty wide.

Dave Pacheco:Please Yeah. Stuff.

Bryan Cantrill:Add stuff.

Dave Pacheco:Great. And and people did.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. And and John, as you're pointing out, like, people all kind of lunged in. Do you wanna describe some of your some of the early things that you built on top of OMDB and how it was important for your own development process?

John Gallagher:Oh, no. Ask me to go back two years. Man.

Bryan Cantrill:Or or you you could just go back to Friday, honestly. If if it's easier to go back to Friday and talk about your most recent stuff, that's fine too.

John Gallagher:Well, think I think maybe the easiest thing to talk about is just reconfigurator in general. Right? So I think

Bryan Cantrill:we have Absolutely.

John Gallagher:Reconfigurator has been a topic on the podcast to an extent, think. Is that right? I Have we talked about that?

Dave Pacheco:I don't think we have very

Bryan Cantrill:much the only way we're gonna know is when we re listen to this after it's edit and listen for a chime. If we don't hear a chime, then we haven't talked

Adam Leventhal:about it before. Wow. You've got a lot of faith in the editor.

John Gallagher:Well, I I mean, I should probably see the floor back to Dave. Dave, do you wanna give some context for what reconfigurator is?

Dave Pacheco:Oh, boy. Yeah. So reconfigurator this this is the shortest version I can do. Reconfigurator is the component of the control plane that's responsible for changes to the topology and configuration of the control plane itself. So if we need to go add components, remove components, upgrade components, and stuff like that, they all go through Reconfigurator, and it uses this plan execute pattern where it creates these things called blueprints, which are pretty complete descriptive descriptions of the system as it should be and then hands that off to an executor that is basically a reconciler pattern thing that will go and make reality match that thing.

Dave Pacheco:And so when you wanna go do a system upgrade, you go through reconfigurator, you go through, like, a sequence of, like, a whole bunch of blueprints and then execute each one. And each one of those is like one step in the change. Does that make sense? Is that a good summary?

Bryan Cantrill:That's a that is an extremely good summary, I feel. And and this problem is important. This is not an abstract problem in in a in a rack scale computer because this is like, you know, if you have a component fail in a sled and that sled needs to be removed, the way the way you actually wanna do is reconfigure the system around the absence of that sled. And that is not trivial to do. That is actually and and when you add wanna add a sled, it's like how how complicated could be to add a sled?

Bryan Cantrill:Just like plug it in. It's like, well, yeah. But now you actually need to reconfigure the system around the presence of this new sled. So this is this is a very concrete problem that was very important to us and to the the earliest users of the oxide rack.

John Gallagher:Yeah. I think to put a really fine point on the thing you just said, what if the sled you just lost was the one that was trying to reconfigure the system in some other way? Right?

Bryan Cantrill:And you

John Gallagher:have to be you have to be able to handle that kind of problem. So reconfigured it right. We've we've mentioned this in passing. It it's it's sort of the underlying system by which we can add and remove hardware, add and remove software, upgrade software components, like all of these things. And for a lot of this stuff, like, we have a we have a mental picture in mind of what we want the operator experience to be.

John Gallagher:Like, upgrading the rack should be you upload the new software, hit go, and then it tells you when it's done, basically, is the sort of the user story of that. Right? But under the hood, it's this very complicated distributed system. Things can fail along the way. Reconfigurator is sort of the the insider baseball of how that's gonna be applied to the rack.

John Gallagher:And it has been we've been working on it for, I don't know, maybe eighteen months is probably the right ballpark.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah.

John Gallagher:And OMDB has allowed us to ship very incomplete pieces of reconfigurator that are still useful for, like, support operations and support operators and also development in a way that, like, we haven't like, the pieces aren't all there to give the operator experience we want yet, but there are enough pieces there to be dangerous and to be useful on a system that needs some kind of minor repair or needs, you know, development in that in in in a way that you need to be able to poke at a live system with both read only operations as Dave mentioned and destructive operations. Like, I need you to go and make actual changes to this in a way that, you know, might be error prone at best to do by hand or even impossible, but we can so I'm sort of rambling here. I'll I'll try

Bryan Cantrill:to No. No. No. Actually, no. No.

Bryan Cantrill:I think this I was almost gonna make you make you repeat this because it is what you've made is such an important point because it it it allow I mean, this is to is to me the essence of this is that the presence of OMDB allowed us to incrementally develop and deploy aspects of the system that don't really have user visible ramifications. It's like how do you deliver something that like you've got this end goal that is a you know, you you've gonna you're gonna put a new foundation in. But there's gonna be a bunch of things that you wanna do along the way that are hard to, like, appreciate and see and hard to, like, demonstrate. And I feel that OMDB was just absolutely essential for all of that. And in turn, like, those demonstrations, I think, were really important for if if if only internally, but I think externally as well.

Bryan Cantrill:But getting the idea of, like, oh, now I get it. Like, I I Dave, I mean, I feel that with some of your early blueprint OMDB demos and being able to, you know, show the deltas between blueprints and kind of, like, what needed to be done to get from one state to the next, it that's very catalyzing for someone who's trying to just understand all of the things that are required for this very complicated change to the system.

Dave Pacheco:Yeah. Totally. And it's it is kind of interesting that we added those commands very early, and I think we've added very few o m d b commands for reconfigurators since then because those commands wind up encompassing what most of what we needed. So, like, we had the blueprint show, blueprint plan or regenerate, which is, like, run our planner to generate a new blueprint and, like, obviously list and delete and setting the target, enabling and disabling. And, like, that's kinda what we needed.

Dave Pacheco:And we kind of built the system around that abstraction to begin with. What changed was what show output and what diff output. You know? Yeah. Like, each new demo had more stuff there and more stuff that was actually carried out by the execute phase.

Bryan Cantrill:And great Ascii art. Is now the time to mention the Ascii art? Because I think the Ascii art is really it's it's really very important. I think the Ascii art is really I mean, it's which I mean, this is the MDB tradition as well, I feel. It's like really killer Ascii art to give you a picture of this to give you a picture in Ascii art of the system that you have.

Bryan Cantrill:Like, I mean, the the colon colon stream does this in MDB. Right? Where you get an actual visual for what the what the stream looks like, which is very helpful to actually kinda map your understanding of the system with its actual implementation.

Dave Pacheco:Oh my god. I don't know what colon colon stream is. What? Really? This is consistent with my thesis that most of us know like 5% of MDB and it only barely overlaps.

Dave Pacheco:Well, every time I'm looking over someone's shoulder, learn some new part of MDB. And and here here I've learned another.

Bryan Cantrill:Well, and I'm I've been just hoping that I haven't, like like, an early version of GPT just hallucinated the whole thing. Like, this is a this is where you'd be like, I I went is no what are you talking about? Oh, I'm so sorry.

Adam Leventhal:You're absolutely right.

Bryan Cantrill:I'm so sorry. Yeah. How can I I so I'm hoping I presuming I haven't hallucinated it? Yes. The also, as long as we're just going back for a quick MDB, Adam, you you did want us to mention colon colon flip one.

Bryan Cantrill:It feels like we I feel like we need to give a tip of the hat to it.

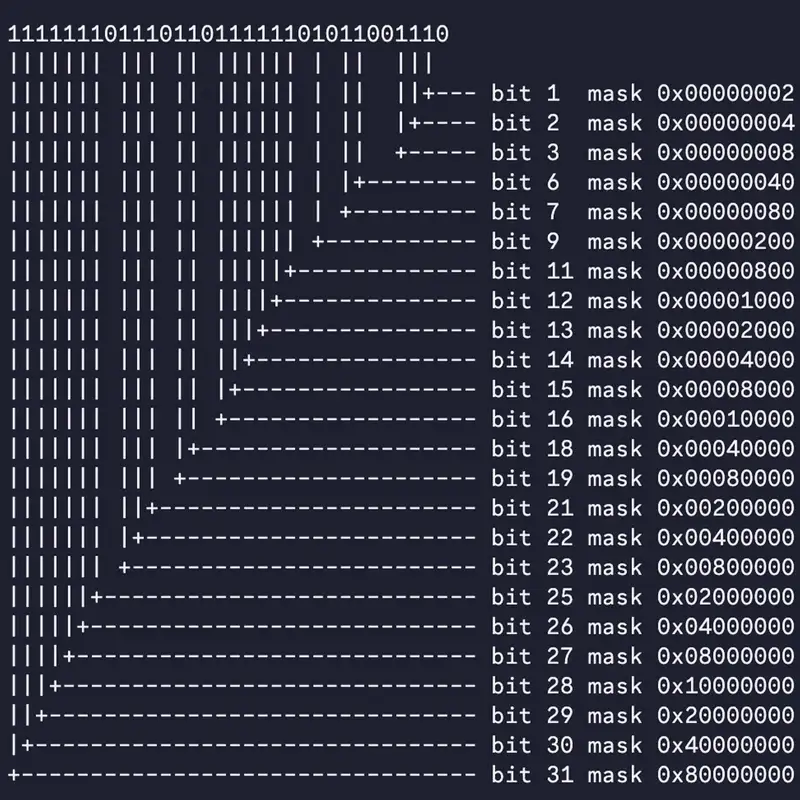

Adam Leventhal:Flip one, it I I got I was looking, know, I I was hired at Sun. I started looking through random d commands, and I found this command flip one, which you give it a number, and it prints out that number if any of its bits were flipped. I'm like, what the fuck is this?

Bryan Cantrill:It it it prints out all iterations with one bit flipped.

John Gallagher:That's right.

Bryan Cantrill:And I'm like, what the

Adam Leventhal:fuck is this? How what is this possibly for? And I feel like it was like, oh sweet summer child, like sit on the floor and gather round while I tell you a tale.

Bryan Cantrill:Tell you a tale about a ship called Viking that had an eyecatch that was not properly grounded out. And that is the the on Viking, the and they ultimately quote unquote fix that. This is like the Viking rev rev level two, which is what is is still in the help message. This is Sun four m, did not have the and this is a bug that Bonwick discovered. So the because the iCache was not properly grounded out, if you and I believe if you had the zeros would flip to ones.

Bryan Cantrill:If you had enough zeros in there Yeah. They would they would start. You'd like, that's a lot of zeros in your iCache. Have a one. I'm sick of zeros.

Bryan Cantrill:It's all zero this, zero that, zero the other thing. And I feel like feel like you need a one. But like try a one. I think it's kind of like, you know, it's like the I actually, Adam, as I was listening to that episode from several years ago, your now elementary schooler was a three year old toddler. Mhmm.

Bryan Cantrill:I'll be interested to see if his future lawyers force us to take that episode down. That'll be I don't I don't know. I'll be just be curious to see how that works out.

Adam Leventhal:Like, real really ring the bell on that one.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. That's right. The chime turns into a Claxton. You got that chime when we reference a future episode. A Claxton when we warn lawyers in the future that they may wanna really carefully

Adam Leventhal:Exhibit it for a crime.

Bryan Cantrill:Exhibit it for a crime. The but the so the and Bonwick discovered this this bug when it's like I mean, and he's got a great tail. And Dave, have you ever heard this? I'm sure yet. This is maybe this is maybe one that's a truly an Australia special.

Dave Pacheco:I don't think so.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, this is an amazing story where so you would because it's in the iCache, you would go to branch to a target and the you'd get a different instruction because you'd slip a bit.

Adam Leventhal:Right. How about outer space? Like, of the intent destination, why not just jump to outer space?

Bryan Cantrill:Why not just jump to outer space? And or or just just jump over here to this other, valid program text for a while and see where that goes. I don't know. That's let's see what happens there. And the and so he would discover that that'd be actually be good to get.

Bryan Cantrill:I'm sure that Jeff still vividly remembers this. But as it was retold to me because this had been debugged before I'd arrived at Sun. But this is when when you have an issue like this, it truly drives you out of your mind because meaningless changes change the the the the presentation of the bug because they change the way program text is organized and changes the actual like address at which particular text is located. Right? So you could do what feels like nothing to the program and the bug would go away when they finally had this thing.

Bryan Cantrill:And Barron was the one who finally cracked this thing open and realized that, if I branch to this address, and again, it was I it's either zeroes flipping to ones or one flip one slipping to zeros, that the he was able to show that I could stuff the iCache with this thing, and it just starts losing bits all over the place.

Adam Leventhal:But you're right. When it's in the iCache, you're like, I look at the debugger state of a live system. I see the value. Yeah. And how could I have gotten here?

Adam Leventhal:Yeah. Impossible. Red light is. Yes. Divergence between data and iCache.

Bryan Cantrill:It's brutal. And the fix for that was to turn off three quarters of the iCache, which is not big air quotes on that one. It's really

Adam Leventhal:kind of Yeah. Mean, the the thing that was astounding to me I mean, was I mean, so many great lessons in this. There was a further lesson in terms of what it taught the field organization. Because for generations then at Sun, salespeople would say, don't you shouldn't buy the extra cash because it really doesn't help.

Bryan Cantrill:Because what they had what they had learned powered off. Cash is bad.

Adam Leventhal:Because what they had learned from this processor was like, I don't know I don't know the details, but I will tell you, like

Bryan Cantrill:Cash is not good.

Adam Leventhal:You don't really get what you pay for on this thing. But it but it was just so interesting to me about how this this oral history made its way through Sun, and out the other side came the Salesforce aphorism, you know, don't really pay for the cash because it doesn't help that much.

Bryan Cantrill:And an m d b d command that we still have. That is actually that is actually occasionally useful. That is the the way you can actually because the reason you want to flip one is because you wanna be like, okay, if I'm at this crazy instruction that doesn't make sense, if I flip one of these bits, is that the actual instructions I wanna be at?

Adam Leventhal:That's right. So the way you run it is you say, crazy crazy value to flip one and then pipe that through, interpret all of these as symbols. If I Yeah.

Dave Pacheco:Call over

Bryan Cantrill:the flip any

Adam Leventhal:of these bits, is any of them a symbol, please? Like, please let any one of them make sense. Yes. It's Exactly. It's gotta be a very dark place when when when you're like, maybe the answer is flip one.

Bryan Cantrill:Cool. And flip one, you're definitely, there are no atheists in a foxhole, think, and this is, you know, I I the the the this is definitely where you've gotten out. You are you are praying to whatever god you've got when you're when you're Cokeland flip one. So, Dave, sorry for the you know, the I'm I'm No. That's great.

Bryan Cantrill:You're like, stop generating. Let's get back to you. Kidding me? No.

Dave Pacheco:I'm trying to get a cold call stream to work. I'm trying to figure out how I can see

Bryan Cantrill:It did not work. It does not exist, of all.

Dave Pacheco:No. No. It does. It totally exists, and I've seen the ASCII art. I just haven't found valid pointer to give it and so I'm only getting the like, you know, a bunch of read errors instead.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. I will I I can get you a walker that will that will walk that will actually generate the the output of colon constraint. That that is my pledge to you. Now that I know that it exists, thank God I didn't lose that whole thing. Never know.

Adam Leventhal:Or it's not some branch on some laptop that you put in the dumpster years ago.

Bryan Cantrill:It's not it's not in Fastrack x. Oh, Fastrack x. What a what a what a what a great repository that thing was. Went down with the ship. Where are we?

Bryan Cantrill:We need to get back to we did we leave breadcrumbs to get us back to the trail? Here we are. I I now I realized now it's gotten dark, and I've got no idea where the trail was. You know, all these all these trees look the same now. Meanwhile, back in OMDB, Dave.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. So sorry. Ascii Art, I think, is where we were. We were talking about the the great Ascii art in in OMDB, which although is now the time to talk about the equals j format character in MPDB?

Dave Pacheco:No. Was thinking about equals j.

Bryan Cantrill:Okay. I you know, I can read your mind. Can you talk can you talk a little bit about equals j?

Dave Pacheco:Well, I'm I'm just a bystander for that that whole thing. I mean, I can tell you what it is and why. It's great. I mean, equals j so equals is the MDB syntax where you give it a value on the left side and you do equals and then a format character, kind of like a printf format character. And j, I believe is ostensibly the jazzed up format.

Bryan Cantrill:Yes. Thank you, Brian.

Dave Pacheco:And I think also Jordan.

Bryan Cantrill:It also for Jordan Hendrix who who was sitting next to me. He's like, know what I would really like? You know what actually be really useful is to actually like I'm sitting here counting bits. I can't remember why she was counting bits. But was like, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:I can like we've got one format character left and good news Jordan, it's yours. It's Jay. So yeah, I think it's jazzed up is is what it supposedly says on the tin. But

Dave Pacheco:It's pretty great. Mean, when you need it.

Bryan Cantrill:It's it's useful when you need it. Yeah. That's it. When you need it, you need it. This is like a lot of these things.

Bryan Cantrill:It's it's when when you need it, you actually need it. And I'm and I'm so glad that we were thinking alike. That we we needed a quick equals j diversion. So now I promise back to OMDB, and it's it's terrific. Ascii are interested more generally, I think that the the printing out, like, the I mean, I can't I think the more general idea is we're printing out this internal state of the system that has no that you wouldn't spend any energy on, like, plumbing this all the way out to the user, but it's extremely valuable to actually understand for the implementer.

Bryan Cantrill:And then I think, John, the reason that your point was so important is because the these OMDB way stations allowed us to see the system as it was being developed, kind of get excited about it and, I mean, really understand what we were doing, get to kind of be able to demo the the these way stations. And that in turn, I think, indisputably accelerated our development. I think that that to me is like the big surprise is that the the the development of you because one might reasonably think that codeveloping a debugger with a system would make the development of that system slower. And I think we would counter that it actually made it faster and more robust to develop the system with the presence of OMVB. John, is that a fair?

Bryan Cantrill:I mean, that that's certainly with the inference that I drew from what you said anyway.

John Gallagher:Yeah. I think that's absolutely right. I I think I would claim there are two reasons for that. One is that adding stuff to OMDB is very straightforward. So there was a there was a chat going back going by that's maybe worth summarizing briefly.

John Gallagher:Somebody asked how do you like, where does this thing run? What what is what does the interface look like? So if you log in to a rack as a developer or as a support operator, you OMDB is a a CLI program that's available as soon as you log in. And by default, it's got a bunch of sub commands for accessing different services in the within the rack. So we've mentioned ondb db, which will access the database and you can run queries.

John Gallagher:Ondb nexus talks to nexus, which is our sort of control plane brain. And by default, if you run one of these sub commands, OMDB will itself connect to our own internal DNS server servers just like any other service within the rack would. So if you say OMDB DB, it'll look up where are the database nodes in internal DNS and then pick one of those and connect to it. But because you have to use this thing on broken systems sometimes, you can always override that and say, the internal DNS check. Here's here's exactly where I need to go.

John Gallagher:The because by default, it can just look up this stuff in internal DNS, adding new stuff to OMDB is basically like, the, like, the the extent of the work is I need to print this thing in a way that is, like, sort of reasonable at a terminal. That's it. I don't have to do any of the machinery to look up services. I don't I've we've already got clients that you it reuses the same clients that other services already use. Like, it's very very fast.

John Gallagher:In fact, in most of our, like, reconfigurator pull request, most of our reconfigurator work, the OMDB changes to support whatever new reconfigurator functionality is landing. They just come in the same PR because it's like, here's an extra 30 lines of code in OMDB that goes with this 500 line PR that makes you able to see the results of this thing in practice. So that's that's one reason that I would say that, like, it's absolutely been a speed boost is that it's so easy to add to. The other is that for reconfigurator in particular, having a system that reconfigures itself, it, like, allows a distributed system to reconfigure itself on the fly, that can go wrong in 10,000 different ways. Right?

Bryan Cantrill:And Right.

John Gallagher:Having OMDB has let us ship things with confidence that it's not going to, like, break in weird ways that we can't understand. And part of that is that, like, we we've talked about the delta between blueprints. Like, this is this is where some of the nice ASCII art comes from. We talked about this on the DAFT episode not that long ago. A thing that we can do with blueprints is I'm gonna I'm gonna generate a new blueprint.

John Gallagher:All that does is produce the new blueprint. It does not make any changes to the system, and then a human can look at the diff before saying, yes, it's okay to move on to that blueprint. And that has been the way we've worked since blueprints were introduced, you know, however many months ago. We're just now just now getting to the point where we're gonna automate this and that that if we had tried to do that, you know, twelve months ago when we started with the blueprints, it would have been a total disaster. Right?

John Gallagher:Because yeah. The several iterations of blueprint were like, are bugs all over the place. Right? It's a new complicated thing. But because we built these sort as you said said, way stations where a human can look at the output and say, okay.

John Gallagher:Yes. This is the plan it's gonna make. Wait. I don't understand what it's gonna do here. I can go ask someone who worked on this part of the system and make sure that this makes sense before I tell the system it's okay to proceed.

John Gallagher:The the history we've built up with that over the last however many months is what's giving us the the don't know if courage is the right word to move forward with automating the thing in a way that we're confident that, you know, we've built enough in here that we can move forward with this.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. That's a really good point. And and because you we Dave, we I remember we often said, so in Choin and and and Oxide too that you you gotta get the human in the loop before you get them out of it. And this allowed us those way stations allowed the these kind of these junctures where you could get the human in the loop for a system that's not totally done yet, but it's got like an element of it is done. A lower level is done.

Bryan Cantrill:The human can get in the loop and audit what they're seeing. And now, John, to your point of, now we've got the confidence where, okay, we've done we can now start start to pull the human out of a loop and get to where we actually wanna go, is this fully automated system.

John Gallagher:Yeah. So we we actually turned we ran the very fully automated test, what, four hours ago maybe? And one of the things it did was weird. We're like, what happened here? But we already had the tools built in to set so what happened was we expected the automated planner to take one step and instead it took two steps.

John Gallagher:We're like, well, that's weird. Why did it do that? But we already had the tools right there to say show me what you did between steps one and two, and then show me what you did between steps two and three. And, like, immediately, within three minutes, we had an issue filed. We knew what it had done wrong because we already had the tools right there from developing them over the last twelve months.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. That is remarkable. That that is really really neat. And I think also think it's been great then for developing totally new functionality that, again, wouldn't have necessarily user visible consequence. I mean, one of those just for me personally was we had all of this sensor data that was coming out of MGS, the managed gateway service, but we had not plumbed it up into the control plane.

Bryan Cantrill:And I just wanted to know, like, is this the information coming out of this correct? And wanted to take the work actually, is where the you know, we we had kiss and cousins with humility bringing humility to OMDB, Dave, where the the Humility dashboard output, which allows us to see the kind of environmentals on a single sled, I brought that in into an MGS dashboard command via OMDB, which is and was basically able to to to really I mean, that code was very easy to go do. To your point, John, of, like, the fact that it that OMDB handled all these things like the service discovery and all this other stuff, where I could then just run that and get a dashboard. And then, Eliza, that allowed you I mean, you were then stitching that up into the control plane. And, I mean, from my perspective, was great to have OMDB to, like, they're like, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:Now Eliza's got something that she can go rig or build on. And then you use this more recently on the FMA stuff. I wonder if you want to talk about, like, what you were demoing on Friday

Adam Leventhal:Oh, yeah.

Eliza Weisman:Without Well, so it's I'm not actually sure if this is the most interesting OMDB use case, but I was I'm I've been working for the last several months on fault management, and in particular, on a component of the system that sort of goes around and collects fault reports from all the service processor firmware. And, you know, I I wrote a bunch of code for doing that last week, and I wanted to be able to show it off and also to test it. And it's actually pretty hard to demo this because it's an it's an automated process that just comes around and collects the error reports periodically. And we've modified the the simulated service processor that we use for control point testing to pretend to have some error reports. And then this thing comes around and sweeps them up.

Eliza Weisman:And in a world where the actual plumbing of that into the alert system is something that's still being worked on by me, you can't actually show off anything interesting about that

Bryan Cantrill:Right.

Eliza Weisman:Because it it sort of does this within the thirty seconds of the simulated control plane coming up. And then it's like, okay. Now these records are in the database. That's great. There's there's nothing I can really interact with here.

Eliza Weisman:So I just sort of went and added a bunch of OMDB commands for printing all of this stuff. And now suddenly, you have a way that you can test that this works, and that's really nice. And especially because the, like, actual, you know, integration tests that I still have to go and write for this are not a very nice demo. Know, you show up at at demo Friday, and you're like, I I would like to show you this system that I've I've implemented. And, the way that I will demonstrate that it works is that I I can run cargo next test, and it says, yeah, all of your tests passed.

Eliza Weisman:And it's like, that's great.

Bryan Cantrill:Which we would still honor. Just for the record. This is mean, we you know, this is a this is a these are systems demos. So, you know, the fact that the, you know, the program runs, the system boots is itself is a is a modern miracle. But I agree with that OMDB allows us to give a little more pizzazz to our systems demos.

Eliza Weisman:Yeah. And it was also very useful because as I was going and sketching out some of these OMDB commands that I wanted to have, I I began to recognize, oh, there are, like, some some interesting it gives you thinking about what are the commands that I might wanna have if something goes wrong gives you a lot of insight into, okay, like, what are the contours of the different different forms of data that we're collecting and storing. Like, for instance, you know, I wanted to do a command that lets you show all of the error reports by sled serial. And that was, you know, so that you could say, like, if this sled has some some hardware faults that it's thrown a bunch of errors. Well, okay.

Eliza Weisman:So it actually if you you go and do this command, you realize it should have a table that also shows you the cubby it was in because the same slide might have been pulled out of one cubby and then later put into a different cubby a different slot in the rack, and you would maybe wanna know that. And conversely, if you want to say, you know, I wanna see all of the errors from sled nine, well, who is SLED nine? That could have been any number of serial numbers at any number of points in time if SLED nine was pulled out and replaced. I picked SLED nine because it is a ill fated

Bryan Cantrill:SLED nine is a SLED number. Yeah. Problematic number. I I don't know. We should see what yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:What what is what is slide nine like? Do a cool quote flip one on slip slide nine, would you? Because that that that's who you seem to be.

Eliza Weisman:You know, and

Dave Pacheco:then yeah.

Eliza Weisman:So it it just gives you this sense of like, oh, here are some things that I actually will want to think about when, you know, the higher level tools are built on top of this. It's like it it gives you a sense of the shape of the data that you might not have thought about quite so intimately if you were not thinking, oh, you know, what are the things that I would definitely want to have if this isn't working?

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. That's really interesting. Where in truly debugger driven development where, like, I'm thinking about what I want. I mean, always, I love what you said about, like, thinking about what I want when the system fails has me thinking differently about the data that I wanna store in the system itself. The and, Dave, I gotta imagine that's been a theme for you as well.

Bryan Cantrill:I I mean, the in the the reconfigurator work and the blueprint work.

Dave Pacheco:Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I'm really glad we got here because this is this is something I've been thinking about a lot. I've been thinking about it a lot. So the when I when the thing I used OMDB for that I remember was the DNS propagation thing, which I don't know if going into that whole

Bryan Cantrill:definitely. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Dave Pacheco:So, basically, the the rack runs in internal DNS and external DNS system. They're two deployments of the same software. So for external DNS, customers delegate a DNS domain to us, and then we serve names under that for the console and web API. And we use that because if we wanna add new IPs that back it or remove some or change them, then we can do that, and we don't have to coordinate with, like, their DNS operations team or something like that. Right?

Dave Pacheco:For internal DNS, we use that to discover all the components within the system. So we run these two different DNS things. And for both of them, the control plane is the authoritative store record of what should be in DNS, like what names should be there with what records and everything. Right? And so the thing that I was working on was the system for configuring for making for having the control plane at large be able to make changes to that DNS configuration and then have that show up at the DNS servers.

Dave Pacheco:And there are so many ways this can go wrong. Right? I mean, knows every outage ever, it's always DNS. Right? And It really is.