A Half-Century of Silicon Valley with Randy Shoup

Hello, Bryan. How are you?

Bryan Cantrill:I'm doing well. How are you?

Adam Leventhal:I'm good. Did you, take the day off or or or hard nose to grindstone?

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, nose to grindstone, please. I'd I, you know, I I would like to think that that the presidents that we honor, only George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, I choose. Yes. You know, I I we call it president's day, but it's only just presidents plural. I feel it's very specific.

Bryan Cantrill:I feel it's just it's just two presidents that we're honoring today. I am. Anyway, that's how I'm observing it today. I don't

Bryan Cantrill:know how you're doing it.

Bryan Cantrill:We're not we're not observing I'm sorry. I'm not observing Warren Harding today.

Adam Leventhal:No. He can get he can get stuffed.

Bryan Cantrill:Warren Harding who croaked in San Francisco.

Adam Leventhal:I did not know that.

Bryan Cantrill:No. Did you not know this? No. Randy, welcome. Did you did you know this that Warren Harding bought it in San Francisco?

Bryan Cantrill:I so actually, I've so I was at the House of Shields.

Adam Leventhal:Yes. Great great bar in in Surma. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Well, so I'm at the house of shields. Who am I with?

Adam Leventhal:O'Grady. Of course.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Of course. Exactly. Right. They're well played.

Bryan Cantrill:So Steven O'Grady is in town. He wants to to so we we go to the House Of Shields. And, we and I start I I bring up Warren Harding, of course, the death of Warren Harding. Why do I bring up the death of Warren Harding? Because Warren Harding died in the Palace Hotel across the street.

Bryan Cantrill:And I'm like, yeah, it's great to be here. It's in the Palace Hotel here to where Warren Harding's final moments on this earth. Last words, I need water. I can kinda feel that's like emblematic of someone not exactly going out on their own terms.

Adam Leventhal:Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Soda and water, and that was the end, the palletale. And, and a Jason Hoffman, you know I both have been on the been on the pod. I believe it was Jason who's who said, you are the only person who knows that. That is so obscure. But, you know, that is really not that obscure.

Bryan Cantrill:Do you know what I mean? Like, this is like a US President died here. Like, this is just not you know, it feels obscure because, you know, Warren Harding feels like but Warren Harding was the president of The United States. It's like, it it was a very big deal. There weren't

Adam Leventhal:that many, actually. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:There weren't that many. Not that many died in office. Not that many died in office in San Francisco, namely one. So it's like, this is a big deal. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:And I'm like, you know, it to the contrary, I think you could walk across the street and and you could any employee at the Palace Hotel is going to know that Warren Harding died in the Palace Hotel. He's like, no way. $20 you're on. I'm like, alright.

Adam Leventhal:Okay. That was an opportunity to really make some money, I feel like.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, stay with me. So we we go across the street. And, of course, the first person we see at the hotel and we would agree that is the first hotel employee we see. And of course, the first hotel employee we see is the concierge. And so I go up to the concierge where Jason and I go up together, and I'm like, sir, a a US president died in this hotel, and I didn't even get to the end of that sentence.

Bryan Cantrill:And the knowing look in that guy's eyes, I'm like, I have this thing, like, absolutely aced. Like, this guy is gonna be able to answer any single question about this guy. So I finished the sentence, died in this hotel. He said yes. And I'm wondering if you might be able to answer some questions about that.

Bryan Cantrill:He said, certainly. And then I think he was a little offended when I was like, what was the name of that president? He's like, come on. It's like, I was hoping for, like, I want, like, a room number

Adam Leventhal:and a time of there's

Bryan Cantrill:so much else I can offer, but he's like and he just says, with just, like, the look that you would give a toddler that thinks they've asked a sophisticated question that has not actually asked a sophisticated question at all, he just says, Warren g Harding, the whatever president he was of The United States. And Jason's kinda dumbfounded, and he's and then he immediately starts, like, well, I mean, that's because it's the concierge. And I'm like, okay. And now this is where you're like, opportunity to really take some money. I'm like, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:Thousand dollar bet. We find someone for whom the question needs to be translated who knows the answer.

Adam Leventhal:Love it.

Bryan Cantrill:And, like, we like, you can find and because, like, you work at the hotel. Like, you're the house keepings. Like, whatever your role is at the hotel, you I mean, it's a hotel. Like, you you you know what the US president died there. It's part of the lore.

Bryan Cantrill:You know what I mean? And he lost his courage. He's like, no. No. I'm not taking that bet.

Bryan Cantrill:And I, you know, I probably overshot. I should've gotten, like, you know, a hundred bucks or something. I I I probably overshot the mark. But so I guess I I am today celebrating, I guess, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and the death of Warren Harding. Not not the life, my dear, but only only the death.

Bryan Cantrill:Standard written presidency. Teapot Dome scandal. Like, the guy was a I mean, he was the you know, how they give each president, that has, like, a nickname associated with him. I was super into the presence as a kid. And yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:That didn't seem earnest.

Adam Leventhal:Oh, no. Go on, please. No. No. That's good.

Bryan Cantrill:I feel like I'm, like, the deep sea garland model. He has said something that does not seem earnest. It may be sarcastic. I will need to ask a further probing question to know if, and the Warren Warren Harding's Warren Harding's nickname was the man from Main Street, which is, you know, and it kinda tells you. This is not this is not a a sparkling presidency.

Bryan Cantrill:This is, but that was when the standards for the presidency were different. And now I would take quarter hour a thousand times. It's like sober.

Adam Leventhal:Man from Main Street, like, you've got my book.

Bryan Cantrill:Man from Main Street. I'll take that. That sounds terrific. I I mean, you just I I I can feel a sense of rectitude just the way you say it. Yes.

Bryan Cantrill:So, anyway, welcome, Randy. Welcome as we celebrate the president's day here, on on Oxide and Friends. So so, Randy, I'm gonna, you know, I we know you're a listener of the pod. Is that is that a fair

Randy Shoup:I may, I can't say long time listener, but I'm a relatively recent time listener, but I've been, binging. And not just because you not just because you invited me, but because so I was a big fan of On the Metal, and then, you know, you guys went dark on that and came back in your various spaces and clubhouses and, you know, ephemeral things. And so I lost track, but now I'm back.

Bryan Cantrill:Now you're back. Well, so so as you know, it it there are many episodes and many, some episodes in which we we we get trolled. We get trolled by a tweet. We get trolled by a blog post. And I know that you have thought to yourself, well, this is good because, like, this is not one of those episodes, but this actually is one of those episodes, unfortunately.

Bryan Cantrill:And it's got nothing to do with the meta ad. Don't worry. I'm not going there. The, the the or or no further there anyway. So the the reason that this is actually the the there is kind of a, an underlying troll here is there was this, and I and again, I I I don't wanna over index on the, more it's more of the sentiment that this, was a tweet, but I've I've posted the the blue sky post in the channel, and it is from, let's just say a young technologist in Silicon Valley.

Bryan Cantrill:It doesn't really matter who, but it's the And the the tweet is, Silicon Valley built the modern world. Why shouldn't we run it? And this is in kind of tacit support of what we are seeing currently in Washington and this kind of this very much, move fast, break things approach to the government, which is breaking a lot of things as it turns out. And, you know, and, Randy, I I imagine I mean, surely, you must feel the same way of just, like, your skin crawling when you have someone who is not just choosing to speak for Silicon Valley, but someone who is so grossly unqualified and speaking in a way that so doesn't represent so many of us in Silicon Valley. And

Randy Shoup:Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Totally. Yeah. Right. Exactly. You're just like, yes.

Bryan Cantrill:That is that is one way of expressing the reaction I'm doing right now.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Look, I mean, feel free to complete your thought. But, yeah, it's crazy. I mean, the fact that, you know, it's this whatever PayPal mafia, you know, slightly enlarged, and the worst of them all that are, like, you know, destroying the republic. Like, that's not great.

Randy Shoup:And then what has annoyed me actually, and maybe told me in this area is, these, like, relative I've written I've read, several articles recently about, oh, Silicon Valley's always been super hard right. Like Yeah. No. No. Have you ever been here?

Randy Shoup:Like, we were like, since the seventies, it's been like hippies and, you know, LSD and, you know, counterculture and changing the world. And it's only relatively recently in the history of Silicon Valley that it has been about money, money, money. And even the people, you know, that have made, all that money, and I there are a number of them, and I know a number of them. For the most part, they didn't start coming here just to make bank. Right?

Randy Shoup:They came here to do things that they cared about. And, oh, by the way, those things that they cared about turns out that, you know, millions and billions of other people cared about and and therefore, we went from there. But I do get my backup, yeah, with this, like, implication that, oh, everybody in Silicon Valley is an Elon Musk or a Peter Thiel.

Bryan Cantrill:That's right. Well, and

Randy Shoup:That's not alright.

Bryan Cantrill:That's not alright. And I think that also I mean, what thing that that I've kind of come to to accept is that and I think something that's important to express is that there are many different Silicon Valleys. And there's a there's a tapestry of Silicon Valley, and there are many different threads through it.

Randy Shoup:We attain multitudes, Brian, multitudes.

Bryan Cantrill:We do contain multitudes. We do contain multitudes. And it's like and the I think for people who haven't been out to the literal Silicon Valley, if if you are out in the Santa Clara Valley, it's barely a valley. It's like a valley is not the term that's gonna come to mind. You'd be like, okay, I see like there is a mountain range over there, and I guess there is technically another mountain range that I can see way over there.

Bryan Cantrill:Is this the valley that people are talking about? It's like, yes, this is this kind of this this flood plain. It's the Bay Area. But the Silicon Valley as metaphor, and, you know, I've often spoken of kind of my Silicon Valley or out of our Silicon Valley, which is, you know, the Silicon Valley of the Traitor's eight or of Xerox PARC or Randy of the Counter Culture. And I I you know, there is there is no one, I think, that is, I think, has got a better perspective on this.

Bryan Cantrill:Or you got a unique perspective on this whole thing, in many different kind of dimensions. So, can we get into your life story for a little bit? Do you mind if we?

Randy Shoup:I don't mind at all. I I I do not have the best perspective, but I do have a unique perspective. So I'll

Adam Leventhal:happily I

Bryan Cantrill:think that that's right. Yeah. I think well, because in particular, so you come out you you not actually born here. You're born, I guess, in in Pittsburgh when your your parents are at what we now call CMU, but was then, I guess, Carnegie Tech. Is that right?

Randy Shoup:Carnegie Institute of Technology. Yeah. Everybody, abbreviated to Carnegie Tech.

Bryan Cantrill:Yep. And you but you come out as your father is is is he coming out to work for Berkeley Computer Company? Is that do I have that?

Randy Shoup:You have that exactly right. Yeah. So, both my parents grew up in Western Pennsylvania around, Pittsburgh, And they met at what was then Carnegie Tech and now Carnegie Mellon University. My dad earned his, undergrad in double e in '65 and then got his PhD in computer science in 1970. And then he Computer science

Bryan Cantrill:in 1970. God, that is a very early computer science department.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. There, I believe that it might be it is, it might be the first computer science PhD program in The US.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. That was Which

Randy Shoup:which might mean in the world. Yeah. So his his, his application to join the PhD program was his, his professor Gordon Bell saying, hey, Dick, I'm starting up a computer computer science lab. Would you like to join it? And my dad's saying, yes.

Bryan Cantrill:So And You

Randy Shoup:know? That was pretty cool.

Bryan Cantrill:Worth elaborating a little bit on who Gordon Bell, was. I think Gordon Bell has passed away. Right? You think that was

Randy Shoup:Yeah. I mean, he's another generation. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:But describe Gordon Bell a little bit because, yeah, Gordon Bell just passed away last year, May of twenty twenty four. But so, a a pioneer of of computing for sure. And just kind of amazing to think of, I mean, the the discipline is still so young, you know, in so many regards that you have. So so he he goes to work for, and then picks up his family and moves moves to the West Coast to go to Berkeley Computer Company.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. So, I was a year and a half. So I was born in Pittsburgh, like I said, Shadyside Hospital right outside, Carnegie. And then, we moved out when I was, one and a half, 19 70. So he's got, you know, freshly minted PhD.

Randy Shoup:We'll talk a little bit about what it's in or I'll just mention. His PhD proposed FPGAs. Like, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:I

Randy Shoup:actually was just looking around in my little archives, which is a, you know, a shelf on my on my bookshelf. And I have an actual print copy of his, of his PhD that was typed by my mom.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, wow. Yeah.

Randy Shoup:Which is pretty cool. I mean, it's a it's a photocopy of it because the original is obviously in the CMU archives or whatever. But,

Bryan Cantrill:what an what an heirloom, you know, to have that is that that's amazing.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. So he he proposed in his, he proposed, I forget exactly what he called it. Reconfigular cell reconfigurable cellular logic. I think that might have been the the title, something like that. Didn't use the term FPGA that came later, but it's exactly that idea.

Randy Shoup:It's, you know, earlier, you know, all computing was phenomenon architecture, so separate, you know, the data from the from the processing. And this was, hey, what if we took the silicon and, like, made it super generic and, and, you know, reconfigured it on the fly, essentially. And it's only relatively recently, like so again, this PhD is 1970. It's only relatively recently. Let's call it twenty two thousands maybe, but certainly twenty tens, where that has become somewhat mainstream.

Randy Shoup:Like, I think there's an Amazon FPGA, service. And then, yeah. And then, Microsoft on Bing, had a project that they called Catapult, which was pairing FPGAs to do the ranking function right next to CPUs essentially, you know, that computed all the search stuff. So anybody who's super interested in that should, Google Catapult. Anyway, but, like, relatively niche, you know, from that perspective, you know, in in the broader ecosystem.

Randy Shoup:Obviously, what you guys would know about and what my dad was originally envisioning was testing new silicon. Right? So, like, hey, let's build the generic silicon and, and then use that to refine, techniques and ideas and then kind of reify those, if that makes any sense.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. For sure. And we we I know it's, I know it's gauche to make reference to one's early on podcast. Although, actually, it it I mean, do I actually believe that because, like,

Randy Shoup:I do it so for you You do it all the time.

Bryan Cantrill:I mean, we do it, like, six times

Adam Leventhal:an episode now, so gauche it up.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Exactly. I'll go shut up. But the, our conversation with Roger Kadoori was so good in that regard, Adam. And that was Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. The and the I ran into Raja, but a a pioneer in his own right, and kinda what the the it just talked about the differences between the CPU and GPU and FPGA and ASIC and kinda when you need these different things and

Randy Shoup:Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:And and soft logic and FPGA has got a very important role to play. So, yeah, kind of wild that your, that your dad is proposing this in his in his PhD thesis. That is that's really Yeah.

Randy Shoup:It's it's crazy. So if you if you track the graph of the papers about FPGAs all the way back, like, they sort of terminate or begin at, at this PhD thesis.

Adam Leventhal:Wayne, I I know he passed a number of years ago. I I watched your talk where he had passed recently. Yeah. And, was he delighted to see FPGAs develop in the way

Randy Shoup:that they did? That's an interesting that's a great question. He consulted on the side every so often for Xilinx and Nice. That's What's the other one? Is it Alterra that might not be right?

Bryan Cantrill:It's Alterra. Alterra well, there well, the other one yeah. There are the, this is where you get the, there are a couple other ones. Lattice is definitely weeping because you you're the the other one you're referring to is not Lattice. It's Alterra.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. And Alterra was was an Intel property. A a and and what the hell? I'm just gonna make reference to our episode on Intel. Sorry.

Bryan Cantrill:Until after Gelsinger. December two. You know, I'm just I'm not gonna apologize for it. You know what? I'm I'm loud and proud

Randy Shoup:about it.

Bryan Cantrill:You should go listen to our Until after Gelsinger episode where I I think we had mentioned out there at least once, but, yes.

Randy Shoup:Yes. So he

Bryan Cantrill:he he so he that that and that's a great question because he I mean, clearly, that I mean, that's an entire industry that he is, like, dip

Adam Leventhal:Can you imagine, like, kind of, like, doing some work as, like, in your early twenties that then turned out to be, like, this whole, you know, I'll make up another billion dollar industry or whatever. That'd be wild. That'd be crazy.

Bryan Cantrill:We we you don't need to Hold on.

Randy Shoup:We're we're not there yet. Yeah. So, so I think he was, I think he was pleased, but it wasn't the crowning achievement of his life by a long shot because Right. Basically, he never did, he never def did FPGAs for Sirius after he completed his PhD. We will fill in the blanks here, but he ended up at Xerox PARC and started most of modern computer graphics, in particular, animation.

Randy Shoup:So, like, there's a direct line from the work that he did at PARC to, Pixar and Toy Story. And even there's a collection to Jim Clark, interestingly, and s and SGI. So, yeah. So what he is known for, is, computer graphics and being again, follow the graph of the contributions back. And he's a very early contributor to, to digital video graphics, which I'll well, I'm sure we'll go into in great detail.

Randy Shoup:But

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. I mean, and it's it's almost understating it in terms of his I mean, he is he he really he's at Xerox PARC. And, you know, Randy, I know that that, you're a big fan, as am I, of Dealers of Lightning, the book on on Xerox PARC. And the, and I I I'm I'm sure you've read it many times, but the the the chapter on your dad, I think, is just extraordinary. And it's kind of amazing to me is that he is actually too revolutionary for Xerox PARC.

Bryan Cantrill:And I think I I was just kinda rereading it today, and I one thing I wanted to ask you because what what he's doing in particular is he wants to build a color display, which is absolute madness in this is, like, in what? Nineteen seventy four or something like that?

Randy Shoup:Yeah. They formed the lab. So he came out to Berkeley Computer Corporation in 1970. It collapsed Yeah. Exactly perfectly for him because Xerox was right then starting up a lab, you know, in Palo Alto called the Palo Alto Research Center or PARC.

Randy Shoup:And the first STIX or eight researchers that Bob Taylor seeded the lab with were people from, Berkeley Computer Corporation. So those include Chuck Thacker, Butler Lampson, my dad. Simone was at Berkeley Computer Corporation, but went elsewhere and then came back to PARC to do Bravo, which later became Microsoft Word. Right. And then Alan Kaye was immediately after those six.

Bryan Cantrill:Just extraordinary. And but then but your dad is at park with this kind of, like, this really personal mission that's a little bit outside the Alto. That's kind of like the you know? Oh, yeah. And and I mean, this must have occurred to you, but I definitely it occurred to me on reread that it's like your dad was like a park within park that in that like your dad was almost treated by Xerox PARC the way Xerox treated PARC.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh my god.

Randy Shoup:So frankly. That's I I mean, obviously, I've thought about this for, you know, fifty years, but, Brian, you've said it, that's l that's you said it perfectly. That's exactly right. In exactly the same way to your point that Xerox, the center, you know, big, Rochester, New York based copier company was like, who are all these crazy long haired California nutcases? And, basically didn't commercialize much of anything.

Randy Shoup:We'll talk about it. They did pay back the lab with a laser printer, but they didn't commercialize any of the other things which included, graphical user interface, object oriented programming in the form of small talk, the first word processor, which is Simone's bravo, Ethernet with Bob Metcalfe.

Bryan Cantrill:You just kept doing it? Like, Ethernet is like, oh, there's a fourth thing. Alright. Ethernet. Ethernet.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, yeah. By the way yeah.

Randy Shoup:I mean, Ethernet's to your Ethernet's not even the first thing that comes out of my No.

Bryan Cantrill:No. It's not even the first thing that comes to mind. It's just insane.

Randy Shoup:Oh, and also email, and, touch screens. But other than that

Bryan Cantrill:But other than that, exactly. Yeah. And but it it it it but even but within that, your dad is too radical for the group. And that you He's

Adam Leventhal:the nutcase's nutcase.

Randy Shoup:He's the nutcase's nutcase. So I'll tell you the story. But, so, people should if they're all interested in this conversation, you should go by and read Dealers of Lightning, which is, 1999, book from Michael Hiltzik about Xerox PARC. There's an earlier one called Fumbling the Future, which is about the business thing that was written in the eighties. That's hard to get.

Randy Shoup:But Dealers of Lightning is amazing. There's a there's a chapter, all about my dad, which is called the Pariahs. And okay. So, Bob Taylor forms this lab, and he came out of ARPA and the whole deal there, and was excellent at assembling really top notch scientists, researchers, particularly computer people, and bringing them all together and getting them to do amazing things. And so that's why he, you know, that's why he was running the lab.

Randy Shoup:Cool. And so he got all these people together. And his his MO is basically tell people to find what's interesting to them, which he told to my dad, and then mold that interest over time so that everybody's all working just kind of in parallel, if that makes any sense or not in parallel, but, like, pointed in the same direction. Like timing? That makes sense.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Yeah. Convergent. Perfect. Yeah.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. So hit so Bob Taylor's, you know, MO, again, I only met him maybe once or twice when I was very, very young. But so this is all, you know, hearsay or whatever Reed say. And, so he so, you know, he formed a lab with all these, like, you know, super top top notch, freshly minted PhDs from around the country and figured that he could mold everyone and point them in the right direction. And he succeeded with the exception of one or two people, just my dad and another guy, Alvy Ray Smith, who's the founder of Pixar.

Randy Shoup:We'll get there. So my dad when they when my dad showed up, Taylor says, take a year to figure out what you wanna do. And my dad Alvy describes my dad in this wonderful phrasing. It's like, I guess I just reread it. It's like, he's kind of a crusty guy.

Randy Shoup:He doesn't play politics, and he's very stubborn. And I was like, got it in one, Alvy. There's a reason why you were dad's, best man that is, you know, when he remarried in 1990. They but they were the best of friends forever. And I'll tell you that whole story in a moment.

Randy Shoup:Anyway, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:So Wendy, do you mind if I did if I just on the Albie Ray Smith because Albie Ray Smith arrives at Park. And do do you mind if I just read out loud the two paragraphs from that chapter from Dealers of Lightning? Because I think that this is really very evocative of their relationship and kinda how extraordinary that time was.

Randy Shoup:Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Park then was at a peak of creative ferment. Each day, some new feat of engineering appeared, virtually demanding to be shown off to anyone of the free moment. And here was Albie Ray Smith, curious as a cat at large with time to spare. Shout fairly tingled with anticipation as he drove to the research center the next morning. Seated next to him was the one man he knew possessed the temperament to get super paint.

Bryan Cantrill:Sure enough, the machine hit Smith like a lightning bolt between the eyes. He came in the door and got completely entranced, Schaub remembered. He just deep ended right into it. For the next several days and nights, the bewitched artist scarcely left the lab for more than an hour or two at a time. I realized this is what I'd come to California for, Smith recalled.

Bryan Cantrill:You could just see it was the future. And and just to think that, like, that's the founder of Pixar, you know, in terms of, like, when he says being hit by a lightning bolt, this is a lightning bolt that has, like, has real ramifications for, like, this is, you know, we this is why, you know, you you your your three year old is singing, you know, so I wanna build a snowman nonstop because it all starts here with a, you know, but just So so let me let me

Randy Shoup:let me motivate this for people who haven't done either have either haven't lived it or or just done the research. So, super briefly, Bob Taylor constructed a lab out of these amazing people. He pointed all of them at the office of the future or something that the other, the, like, chairman or CEO of Xerox said, the architecture of information. Nobody knew what that meant, including that guy. But but but, but everybody was excited about it.

Randy Shoup:And so everybody so all the things that I mentioned, right, graphical user interface, object oriented programming, Ethernet laser printer, all those things, you know, direct line to Office of the Future. So you could see how all that research, you know, combined. And it totally did in the, Xerox Star, then the Apple Lisa, then finally the Mac. So we we can see the direct thread, you know, from everybody else in the lab. My dad, again again, because he was told he would have a year to think about it, he took it only took a month.

Randy Shoup:But he's like, I wanna do color graphics, and I want to do video. So I wanna be able to use this new cool technology called the frame buffer with these, with these new, massively new pieces of hardware called semiconductors made by a little tiny company in the valley called Intel. Yeah. And because they made memory then, not, wasn't wasn't even CPUs yet. And he wanted to construct the world's first, not the first paint program, but, like, he wanted to construct he wanted to combine a paint program, a few people have played with that, with a frame buffer, a few people have played with that, with being able to take in video at frame rate, 30 frames a second, manipulate it digitally in the frame buffer, and then send it out the other end at frame rate thirty thirty frames a second.

Randy Shoup:And so that's what he built. So he built a frame. So if you haven't heard of a frame buffer, it's very obvious what it is. You take a frame and you put it in a buffer. And this particular buffer was intended to be exactly the, what is it, six eighty by no.

Randy Shoup:Six forty by four eighty six for of it, which is a standard television, you know, ratio. And, so if you multiply that out and you give yourself one byte, eight bits of color, So 20, you know, 256, color depth essentially. Then you multiply that out, it comes out to 300 and something thousand, bytes. And so Intel was just shipping two kilobit, shift registers shift registers, put a pin in that, not DRAM, but shift registers. And the frame buffer that, dad built called, the system overall is called SuperPaint.

Randy Shoup:The frame buffer that was, you know, the core of the system was a bunch of these shift registers all chained together to be one long massive virtual shift register of 300 and some odd thousand bytes. And the way that it worked is associate it was like shifting along byte by byte chunk chunk chunk chunk. The video comes in, it gets manipulated, and it comes out raster scan. So people know how television works. Right?

Randy Shoup:The raster scans one direction, then it scans the next direction, one lower, then it scans the next direction, one lower, etcetera, back and forth and back and forth. And that, snaky back and forth that the raster does was represented directly one byte each, in, in memory. And so the system, the paint system was all, manipulating those, those bits digitally. And so what was amazing this is 1973, '10 years eleven years before the Mac. Nineteen seventy three, he gets this working in April.

Randy Shoup:And the way that the system so anybody who's used any patent program has used exactly this metaphor invented. There you go. It works sort of. It used, used, anybody's used a, patent program has used something, you know, exactly analogous to this. And it's basically the metaphors that he, in collaboration with few other people in the lab, came up with.

Randy Shoup:So it's, one, part of it, it was actually one television screen. So one television was the canvas where it's where you draw and stuff, but the other was the, the palette. So you choose your color, you choose your brush size and shape. You choose various effects, various animation effects, and then you go over using a stylus on a massive tablet as opposed to a mouse, but other stuff was done doing using a mouse at park. So you use a stylus on a tablet, and you go over into the onto the canvas and you draw things.

Randy Shoup:And that was the thing. So now I'm kind of now it's maybe motivating why Alvy was so amazed. Alvy Alvy was, had a PhD in computer science. Also, he had been a mathematics professor at NYU, I wanna say, had a really bad accident and then, like, totally rethought his life and got in his, I don't know, VW van or whatever it was and, like, you know, drove across the country to visit his pal, Dick Shop, and try to figure out what's next for his life. And, you know, that's the hit like a lightning bolt.

Randy Shoup:You know what I mean? It was sort of, like, very fallow ground, if that makes any sense. You know, like, he was he was he was wrecked. I mean, he had all the, like, again, PhD in computer science. The guy's a freaking rock star.

Randy Shoup:And, so very ready to appreciate and understand all aspects of this from a computer science perspective. But also, he's a he's an artist and a painter, you know? So that's why that's why the the clip or, you know, the quote that you gave, you know, my dad saying, you know, it was one person who could understand it. Again, understand it technically, but also really appreciate it artistically.

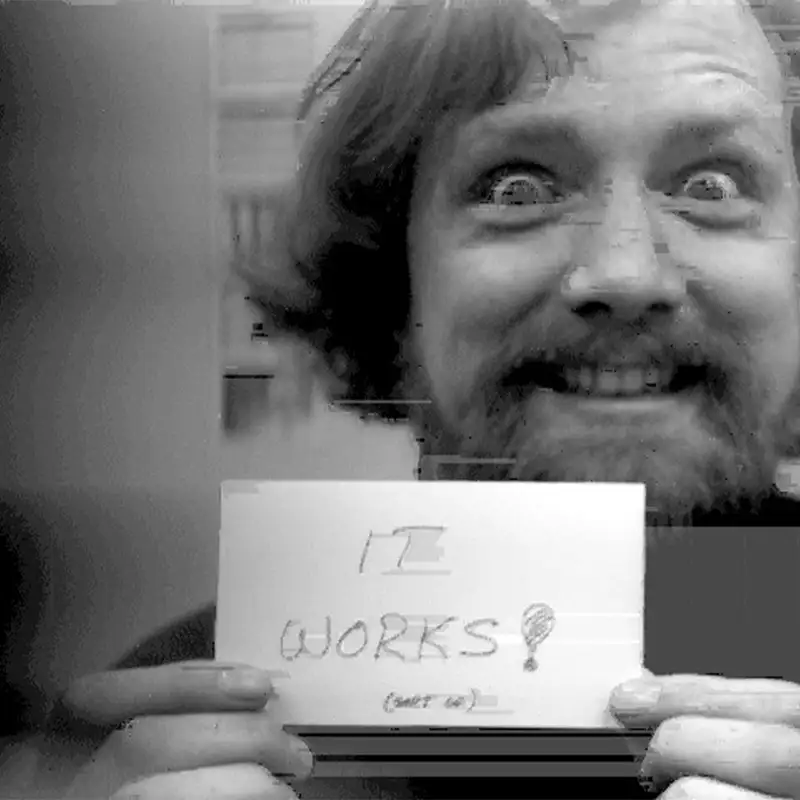

Bryan Cantrill:And I I dropped this this image in the chat, but the the image, it works, bang, underneath written, sort of. Your dad holding it holding it above. And that is this is an image from the actual system. Right? I mean, this is the

Randy Shoup:So yeah. Sorry. So, yeah, this is April 1973. So, obviously, nineteen seventies. Look at the you can't it's a gray scale, but it's flaming red hair.

Randy Shoup:And, so this is the very first image that was taken by, SuperPaint, and he had not yet debugged the so it's it's using a a data general 900, something like that. I don't know. Using some mini mini computer of the time, and,

Bryan Cantrill:he he

Randy Shoup:has he hasn't that's it. Did you know him exactly right?

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah.

Randy Shoup:He, and he is, he has not yet he's gotten the frame buffer, but he hasn't yet debugged or even hooked up the, DG system. So he took this picture because he finally had the frame buffer working. He apparently needed to pull apart or put the clip leads back on with his knees so that he could get this image. So now so it's on and the image is in memory and until and before it degrades or whatever, he needs to because he wants to save it. He wants to he, like, now connects up the interface to the, DG Nova and debugs it because it's super complicated and figures out how the interface works, and writes the code for it's like he's writing the code on the fly.

Randy Shoup:I don't know, like some, you know, hacker stupid hacker movie. He's writing the writing the interface code on the fly in, of course, machine code, to to, to save this image, and it works, sort of.

Bryan Cantrill:And and this is, I mean, just and this is an extraordinary moment in the history of humanity, not to put I mean, this is this is like Alexander Graham Bell, mister Watson, come here. I want you. I mean, I feel it's like the it's just in I mean, this is, a this is a breakthrough. And I I you know, the fact that he's having to, like, you know, manipulate it with his feet shows what I mean, he was working by himself on this, really. I mean, this is like Yeah.

Randy Shoup:He he def he definitely had help from a few other people in the lab, but everybody, you know, he's a pretty modest guy, but, yeah, he did it all himself. I mean, you know, he had he had a bunch of help on a few things from a guy, Bob Flagle in the lab and, Patrick Baudelaire, I wanna say. But, but, yeah, he mostly did it himself. And, you know, he's 30 years old, at this point, not quite 30.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Oh, wow.

Randy Shoup:And then Wow. We'll we'll do all this if you want. But, like, fast forward, he won an Emmy for this. Ten years later, television Emmy, and then he won an Academy Award, a Science and Technology Academy Award. So not an Oscar because it's not a statuette, but a Science and Technology Academy Award in 1998 for this work.

Randy Shoup:And so, again, we mentioned Alvy Ray Smith as being his, his collaborator and, like, his, you know, most excited fan or whatever. And they collaborated for a number of years at PARC. And then, you know, over time, people left to go found their own things, including Albie. So Albie went to, New York Institute of Technology and, hooked up with Ed Catmull, who had been doing graphics at Utah. And then they ultimately, got themselves, acquired into become the computer group at Lucasfilm.

Randy Shoup:Lucasfilm. And then, let's see. Then they did, they were hoping they were planning to do something for Empire Strikes Back, but, Lucas didn't want to. They did do something for Return of the Jedi, but their famous calling card was the, Star Trek two Wrath of Khan 1982 Genesis effect. So people will remember watching the Wrath of Khan, will remember the Genesis device.

Randy Shoup:It's it takes a dead world and turns it into something living. So, so that whole it's like a two minute sequence is the first fully computer generated animation sequence in a major motion picture. And with that calling card, they ended up doing a bunch more Lucasfilm. They spun themselves out as Pixar. Steve Jobs got involved.

Randy Shoup:Toy Story, back to just, you know, acquired by Disney later in life. But that's, you know, super that's a super quick thread there. But yeah. Oh, and and the and sorry. Let me just finish this up.

Randy Shoup:Sorry. Yeah. How did so the the television Emmy was a thing that, you know, SuperPaint was used in a bunch of television things, including by NASA for the Pioneer Venus mission in '77, the Pioneer Saturn mission in '78. So, like, it was known in television that this thing existed, but he wasn't but dad never did anything in movies. Right?

Randy Shoup:So why would the academy, you know, award him a lifetime achievement award? Well, it was with Alvy and another guy, Tom Porter from Pixar. And it was because in 1998, the academy went to the Pixar folks and said, we would like to give you a lifetime achievement award. We think you've earned for Toy Story and the whole deal. And Alvy, to his great credit, says, sir, happy to take that, but you also have to find this crazy guy, Dick Schaub, and give him the same award because Superpaint, because this inspiration, and so on.

Randy Shoup:So

Bryan Cantrill:Which I think is, I mean, such inspiring in so many different dimensions. Because I mean, I think that, like, the, you know, the the kind of people the way people commonly think of Park as, you know, Steve Jobs kind of descends upon Park and realizes that they're gonna kinda fumble the future, and and and does the Lisa and and like, and the kind of the the kind of the narrative is this kind of not giving credit where it's due, perhaps to to to the Alto. And I just I I kinda love this, like, other narrative of this this kind of park within park. This person is too renegade for the rest of park. Right.

Bryan Cantrill:That Bob Taylor's like, what what are you doing over here? Like, what what this is not this is not when I said pick anything that you want, this is not what I meant. This

Randy Shoup:is I didn't actually mean it literally. Oh my god. I'm sure that was exactly the conversation that was had with my dad many, many times. And, again, like, to quote Alvy, like, he's very stubborn.

Bryan Cantrill:Right. Well, he and I I mean, so so Bob Taylor is an enormous, like, inspiration to me personally in terms of, like, the way he got people to take on really hard problems, I think is is really inspirational. And I can definitely understand, like, the Bob Taylor perspective of this of, like, look, I mean, yeah, we're trying to, like, we're, you know, we're we're pretty crazy, but, like, we're not that great. You're you're actually you're kinda two hills further ahead of us in a way that is, like, really tough. But I and I also just love this kind of the the fact that Alvy Ray Smith really wanted to make sure that, like, your dad got the credit that he was due, that this was it was not about, like, stealing the work of someone else or or or I mean, I just I think it's really, and I mean, when when I say, like, I mean, that is just it's that's a it is a great Silicon Valley story in terms of, very inspiring.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. It's exactly the opposite of the current, those articles we were talking about in the beginning. Right? So, like, Alvy could have said, yeah. I invented, you know, computer animation.

Randy Shoup:And, like, he wouldn't have entirely been wrong. Right? But every time he's interviewed, I mean, any Google anything that Alvy says about his background, he will, in the first paragraph, say, yeah, I was really inspired to you know, I was doing a bunch of graphics and I was interested in this area. But, you know, until I saw Superpaint and got inspired by Dick Schaub, you know, I didn't see I didn't see how it would be the the next, whatever, multiple decades of my life. You

Bryan Cantrill:know, and, and yeah.

Randy Shoup:And yeah. So I mean, exactly. Credit credit where credit is due, but in a wonderful I mean, Albie's wonderful. Like, a wonderfully humble and, I don't know, confident, if that makes any sense. Like, Albie Alvy's got accolades up and down and left and right.

Randy Shoup:Like, he

Bryan Cantrill:does his He yeah. I mean, he's like, I'm not worried about, like, I'm not taking anything away from myself by sharing by giving credit where it's due. Like, I've yeah. I've got total self confidence. I also feel like that there's something really about the fact that, you know, there at the moment, right, like, I know I know what the before times were like.

Bryan Cantrill:I know what the after Like, I was there when this was created. This is not and I think one of the challenges that we've got in Silicon Valley, and this maybe this has been true at different times in Silicon Valley's history, but this idea of and you you see people who who have inherited wealth, who pretend that they built it themselves. It's like, everyone should, you know, it's like, well, you didn't build the stuff that you're talking about. And, you know, you like, when you say Silicon Valley built the modern world, why shouldn't we run it? It's like, who who

Randy Shoup:are you? I'm sorry.

Bryan Cantrill:Right. Right. Is that Bob Taylor saying this? This Yeah. Right.

Bryan Cantrill:Exactly. Bob Noyce? Is this are you Gordon Moore? Are you I mean, sorry. You didn't build any of these stuff.

Bryan Cantrill:You put a hair into it, pal.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. No. That's that's a % true.

Bryan Cantrill:Like, this is this is daddy's money. And, you know, you and I get it. Like, on the one hand, you know, I wanna allow people their own, like, search for meaning and, like but, I mean, come on. I mean and I I I feel that, you know, we all have kind of a challenge of, like, when we've got these kind of great contributions that kinda come before us and how do we get kind of inspired by those and build the next thing while still understanding how how fortunate we are for those, you know, the the that kind of ancestry that solved all these hard problems.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Look, everything everything in a modern computer I mean, you you know more than anybody, you guys, at Oxide. Right? Everything in the modern computer setup, any modern computing system, is layer upon layer upon layer of outrageous invention and discovery and science and hard work and, you know, perspiration in addition to inspiration. Like, the multiple every layer is, like, there's somebody whose life's work was that thing.

Randy Shoup:And we have now I'm making this up, and you would know, like, okay. There's a hundred layers or whatever. Right? Like, every single you're right. You know what I mean?

Randy Shoup:Like, every single and you're, like, that's only the firmware.

Bryan Cantrill:It's like You know, when also, like, on the one hand, it is kinda like, okay. No more layers, please. Like, I need I I need because the other thing that we've discovered in, of course, in oxide is then, like, you you get down to enough layers and then the world goes analog again. You're like, what's this? It's like, oh, yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Sorry. Digital's a lie. Wait. What do you mean digital's a lie? It's like, no.

Bryan Cantrill:No. That's what you saw for people need digital, so we created but it's actually this is an analog system. You're like, that is extremely unfortunate. So, yeah, the layers never stop. There there there's a there is an infinity of layers, but, yeah, just to your point, Randy, like, the, you know, when you get into, like, build building these things, you get that kind of reverence for all the stuff that comes before you.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Yeah. And I think, you know, there's I'm I'm not I'm not unaware of the, like, self serving aspect of this, But, like, I do not think that people today fully understand how much of current software systems that they work with owe everything to park. Right? And again, not even my dad.

Randy Shoup:Right? Like, again, my dad to your point and it's correct is like an offshoot of an offshoot. Like, he, you know, his his work, as he would say, did not figure in the main line of Alto to star to Lisa to Mac, etcetera. I'm like, that's fine. He was he felt happy with what he did.

Randy Shoup:But but I think it is way underappreciated by particularly the younger generations. Right? You know, get off my lawn. How much how much in 1973 was there? And it took it it was so far ahead.

Randy Shoup:I mean, it took ten years minimum. The IBM PC came out and there was nothing graphical about it. Right? That's ten years. So Yeah.

Randy Shoup:It took it took till the Mac and, you know, amazing, but still and this was, you know, quite the long like, the part people were looking at going, a, we had that ten years ago, and, b, what a toy. You know, ultimately, not one. And, you know, breadth versus depth, if that makes any sense. Like, right? I mean, it went it it went viral and did the personal computer that Alan Kay wanted to build.

Randy Shoup:But, yeah, I just don't think, you know, I just think think I don't think we appreciate enough the giants upon whose shoulders we stand, if that makes sense.

Bryan Cantrill:I I totally agree with you. And so one question I've got with you too about in terms of, like, the breakthrough because of the to me, the breakthroughs at park are not merely technological, but they're also cultural and organizational. And these are breakthroughs that I'm and this is maybe a good segue to kind of your own career. Well, first of all, I've got I mean, this is a little intimidating to have this as I I I mean, this is, like, no pressure, by the way, but, like, aren't you Dick Shops kid? Like, you know, I'm I'm I'm kind of like, what was it like growing up in the shadow of that?

Bryan Cantrill:Or or or or does is is this like this is actually this is actually a relief that this is it stands so tall that I actually don't have to worry about, like, my own sense of intimidation. What what was it like?

Randy Shoup:Yeah. I mean, all of the above. So, when I was growing up, I saw I was always interested in math and computers, and I didn't appreciate how different it was to I mean, no one appreciates how different their family is until they have experience with other families later in life. Right? So I didn't know it was weird to be a five year old and to beg your dad to take you to work on the weekends, which I totally did.

Randy Shoup:So my parents were my parents were divorced when I was four, but dad was around and, we, my brother and I would would be with him on weekends most of the time. And he would work because, hey, he liked to work. And we could not have been happier to go to park because when we were when we were babies or even babies, not babies. When we were little, we used to play in the beanbag conference room and make forts. And then later on, really, in retrospect in retrospect, his was the only work that would appeal to, like, a five or six year old.

Randy Shoup:Right? So he's building this. Right. Right.

Adam Leventhal:You were getting screen time before any other kid was getting screen time.

Bryan Cantrill:That's right.

Randy Shoup:I yeah. And I and I didn't know that again, like, wait. Don't you beg your dad to take it? No. My dad's a teacher.

Randy Shoup:Like, yeah. So, you know, we would we would beg him to take us to, to work and, you know, we would, again, play in the beanbag, room when we were younger. And then, there was a a Star Trek simulator thing, which, of course, we love to play. And then as, my dad's stuff with super paint came along, yeah, we would drop pictures of spaceships, and then we would print them on the laser printer in color. Oh my god.

Randy Shoup:And and so the one time he told me not to, like, divulge anything was when we printed out the color, thing from the laser printer, he's like, maybe don't show this to anybody from IBM.

Bryan Cantrill:And what year is that? I re I re

Randy Shoup:gosh. Let's see. Maybe '77.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, my god.

Adam Leventhal:I'm just imagining my seven year old showing up with, like, a laser printed drawing and just can't like, imagine, I just can't even imagine what it would be like to bring that to school in that era. It's like walking in with a bar of gold or something. Just, just unimaginable riches.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Or or or the company just go into hovercraft. I mean, this is, like, 1977. The the this is, like, the laser printer would not be broadly commercialized for another decade, and that's black and white. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:I mean, like, you I mean, I remember, like, literally seeing the first laser printed thing by the a, a a friend whose whose father was a software engineer, had a laser printer at work. And I printed I printed this thing out, had the laser printed, whatever, like, an an agenda for a scout meeting or whatever it was. And I remember, like, just my eye I mean, just eye popping.

Adam Leventhal:No perforations on the edges. No. You're evil.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Right. Right. So, it was a dot matrix.

Bryan Cantrill:Contrast, like, a dot matrix printer to a laser printer. You're like, this is like you took this to a professional printer? It just doesn't make sense. I mean, it was and that was in, like, 1987. I mean, it's like in 1977, you had and it was a black and white.

Bryan Cantrill:I mean, I just think that, like I think I mean, you literally start a religion on the spot. Like, no joke. You'd be like, you like, you Randy, like, I I think you had the opportunity to be a prophet. I think you could have been, like Oh,

Randy Shoup:so many missed opportunities.

Bryan Cantrill:You could have been, like, the the the Randy Farians. Like, didn't they I thought that it was, like, a wasn't there, like, a rituals. It wasn't or something that they did. No. No.

Bryan Cantrill:No. The Randy Farians were the, but They

Randy Shoup:were they prayed to the laser printed, Absolutely. Gods.

Bryan Cantrill:The spaceship gods. I would have a % would have prayed to the spaceship gods. If you showed me a color laser printer in 1977, that is absolutely Yeah. Unthinkable. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Unthinkable. It is unthinkable. I there there is no modern analog that's gonna, wow. That is amazing.

Bryan Cantrill:I also love that you're, like, making beanbag forts in Xerox Park. I mean, at what point were you, I mean, in your kind of you know, so you you you obviously, you grow up in the Bay Area, you grow up in Mountain View, or I get where you're at San Jose. Bay the this Palo Alto and San Jose. Palo Alto. Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:At what point were you just like, wait a minute. That was Xerox Park that I was I I mean, you must or or did you maybe you had the sense of gravitas at the time. But, No.

Randy Shoup:I really didn't. I mean, yeah. I mean, when you're a kid, you're a kid. You things you know, whatever your experience is seems normal. So I only really it only real I mean, I knew it intellectually, maybe in let's call it in junior high and high school, but it didn't really hit me maybe until college or later just how very, very different, you know, that experience was.

Randy Shoup:Right? Yeah. I mean, again, you know, we all, you know, we all stand on shoulders of giants. Anyway, but you're asking

Bryan Cantrill:the question. Making beanbag forts in, like, Faneuil Hall or something. I'm like, I'm trying to what is the analog for this? It's like, it is it it it kind of anyway, it defies analog. It's it's just really

Randy Shoup:extraordinary. I mean, I don't this is only an analogy that I just thought of, and I don't know if it works. But you could one could imagine growing up in a royal family. And so this was not our case. You know, we were we we were very middle class.

Randy Shoup:You know, one thing one thing dad never did was make a huge pile of money, which is, you know, fine. He had a great he had a great life. But yeah. No. I mean, I guess if you're talking you guys are reacting in the way that you're reacting.

Randy Shoup:And the only thing I can think of that comes immediately to mind is, you know, somebody that grows up in some, like, actual castle. Right?

Bryan Cantrill:And I was like, Oh.

Randy Shoup:Well, you know, I walked out and we had the the the horse carers, you know, brought the horse for the day, and then I rode

Bryan Cantrill:Right.

Randy Shoup:Rode it and blah blah blah.

Bryan Cantrill:Or I'm in

Adam Leventhal:the presence of Sasha and Malia. You know, like

Randy Shoup:There you go.

Bryan Cantrill:Coming to

Randy Shoup:baseball. Yeah. Exactly. Whatever. What yeah.

Randy Shoup:Show and tell. Big fans of the pod.

Bryan Cantrill:Big fans of the pod. Those those two.

Adam Leventhal:That's right. Call anytime. You we'll we'll have you on.

Bryan Cantrill:Exactly. Love the baseball one. Absolute big ballers fans. Those two.

Randy Shoup:So anyway, you you do ask quick I'll just quickly answer, like, what how much of a conflict or in terms of expectations. And as I like to quote from the, Tom Mariasi of Car Talk, happiness is reality minus expectations. So expectations were higher. I mean, look, I already tick all the privilege boxes. Right?

Randy Shoup:You know, white male, hetero, grow up in a strong economy, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick. You know, so the expectation should already be higher. But, yeah, you know, debt set a pretty high bar. And also, he never I don't know how to feel about this, to be honest. He never once placed any expectation on me or my brother.

Randy Shoup:And part of me, it's like, wait, you don't think it could be as good? It's like, well, maybe not. So, you know, it kinda goes both ways, I suppose.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. That's why but did you know is I mean, you're interested in this stuff. Did you have any reticence about going into computer science?

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Actually, so I didn't. Yeah. So my, and this wasn't because I was scared away, but I just thought my talents were elsewhere. So, very briefly in high school, I did debate.

Randy Shoup:And so, like, all but one other person I can think of who is, you know, that I knew from high school debate, I was planning on becoming a lawyer. And I wanted I was super interested in international relations and, you know, that time's height of the Cold War. So I was really interested in reducing the tens of thousands of nuclear weapons that, you know, The US and The Soviet Union had pointed at each other. And so that was a real thing that I really cared about. And, so my things don't always work out as you expect when you're a kid.

Randy Shoup:So if you asked me at 13 all the way through to 23, I would have said my career is to be an international lawyer. It turns out that, so I majored in political science at Stanford. But I also wanted to study math and computers because I was always interested in them. And thankfully, Stanford didn't have minors when I went because otherwise, I would have gotten a minor and fine. But instead, the only way to to do it seriously was to double major in mathematical and computational science, which is was like nobody took did that.

Randy Shoup:It was like a handful of us in that major. It's not wasn't the computer science major. Even then that was not that many. I hear it's like the, you know, a third of the school is now

Bryan Cantrill:computer science major. Right? I

Randy Shoup:mean, not even not even joking. Not even joking. So now the now the major that I had is the data science major. But Oh, interesting. But anyway, whatever.

Randy Shoup:So I had so I had you double majored in the two things. And then during, during school for another weird set of coincidences, I ended up interning at, Intel for several summers, and so got a taste of as a software engineer, so I got a taste of doing software at Intel.

Bryan Cantrill:So so you were interning in even though you were a poli sci concentrator, because you'd taken enough computer science courses or you'd you were able to and realized, like, okay. This is what I wanna do with my

Randy Shoup:I I did not ever lie, but I bluffed as hard as I possibly could.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. So I will

Randy Shoup:I will tell the story because it's funny. So my roommate, sophomore year was a double e. Weirdly, he he studied double e and is now a lawyer. I was planning to be a lawyer, and now I'm a computer computer guy. So Love it.

Randy Shoup:I don't know where Stan z went is wrong, and I went right or She's a different guy. Yeah. We were we we crossed the streams and went entirely different direction. Anyway, so Stan was a double e and very good at it. And so, I'm reading one of my poli sci books and he sets the phone down in the room and he says, hey, this is weird.

Randy Shoup:I said, what? He's like, well, you know how I just got an this is like fall of the sophomore year. He's like, you know, I just got an internship at Intel for the summer. I'm like, yes. And he says, well, I just got another.

Randy Shoup:I'm like, what? And the story was the guy so he had, applied to several. A guy said, please, hire Stan and then went on vacation for three weeks. And then when he came back, he, you know, he said to the whatever executive assistant or whoever, hey, did you hire Stan? And, like, forgot to do that.

Randy Shoup:Anyway, so they called Stan back.

Bryan Cantrill:After lied, but I did go by Stan for two summers.

Randy Shoup:No. Not quite. So,

Adam Leventhal:I just responded to Stan. I didn't tell you that. That's right.

Bryan Cantrill:It is your inference that my name is Stan because you called out Stan and I responded. That is like, that's on you.

Randy Shoup:That's right. No. I did it I did it above board. So Stan so Stan had already taken another job, another internship at Intel. And so he said, do you know anybody who would want this internship?

Randy Shoup:And I was like, well, I you I had applied at the arms control center, you know, to work over the summer, but they haven't gotten back to me. So sure, let me, you know, let me talk to them. And so I ended up, you know, working really hard on talking about all the math classes that I had taken and, you know, the the the limited computer science and, you know, really tried to, impress upon the guy who became my boss that, I could learn things and, oh, by the way, my dad does this stuff, so whatever. And, anyway, so

Bryan Cantrill:he he later Oh, I okay. I I definitely have a question on this. No. Because, like, dropping the dad references is gutsy. Right?

Bryan Cantrill:That can backfire big time on you.

Adam Leventhal:Totally.

Bryan Cantrill:The I I I I

Randy Shoup:didn't know. I all I knew was this is a like, hey. I've been around computers for a long time. My dad used to do this thing. And,

Bryan Cantrill:So my analog to this actually is I sliced my nose skiing. So I I I was skiing and I I was kinda mid air and deep deep snow. I come out of my boots and fly, and I know my skis are still going, and they come up behind me and slice my nose. My my skis did.

Randy Shoup:Oh, okay.

Bryan Cantrill:And so I'm bleeding kind of profusely out of my nose, which is just like a lot of blood. And I need to go get stitched up. So I'm in the the the Tahoe emergency the the Truckee clinic there. I'm about and I'm about to get stitched up. And, the And actually, I mean, in in some strange ways.

Bryan Cantrill:So my father's an emergency medical physician. And emergency medicine is actually, like computer science, is very young. And my father ended up being, working in one of the the first residency programs in emergency medicine and for the the pioneer really of emergency medicine, Peter Rosen. And he, they were writing the book on emergency medicine. He's just doling out chapters to these, like, kids.

Bryan Cantrill:And my father ended up writing the chapter, well, wrote a bunch of chapters, but one of the ones is on facial lacerations. Yeah. And so here I am with a facial laceration, and I'm like, do and one thing I definitely knew is the the scarring that you're gonna get is based solely on the hands that are on you. It is the if if someone is is paying attention and has got is got is is dexterous, you will not have a scar. And if they aren't, you will have a scar.

Bryan Cantrill:So I'm like, I have got kind of like a very limited window. Like, do I name drop this or not? And the needle is coming at my nose as this guy's gonna stitch me up. And I'm like, suddenly, this could backfire. Like, what what is kind of a snotty thing to say?

Bryan Cantrill:Being like, oh, by the way, have you heard of my dad? But I'm also like, but this could be a scar I could have, like, on my nose for the rest. I could be, like, known as Scar Nose for the rest of my life. You know? So I'm like, You know, it's funny.

Bryan Cantrill:And he kind of stops. He's like, What's funny? I'm like, Well, you know, here I am. I've got a facial laceration. I'm in the emergency room.

Bryan Cantrill:I've got a facial laceration. Just a regular Cantril. Just a regular guy with a facial laceration. And, you know, it's funny because my father actually wrote the chapter in Rosenparkon on facial lacerations. And he's like, Oh.

Bryan Cantrill:And you could just see And I'm like, It's backfiring. This is a mistake. Like, I could just see the guy is like, Are you fucking kidding me? Like, what are okay. And and he says, who's your father?

Bryan Cantrill:I'm like, Steve Kenter. I said, oh, Steve Kenter from Colorado General. And he had done a residency. He'd been in Colorado General. And I'm like, oh my god.

Bryan Cantrill:Okay. Okay. This is like diving catch though. Like, total diving catch. And I'm like, this could have, like so you Ray, did you have any of the same nervousness?

Bryan Cantrill:I'm like, do do I mention that I'm like that I'm that I'm related to Dick Shoup. Do I how would I do this?

Randy Shoup:Yeah. I wasn't so strategic. I just thought I was trying to get an internship. And, and, anyway, it ultimately worked. So and and but it later, Bob Chen, who was my boss there at Intel, was like, yeah, I could read that you didn't really he didn't quite say it this way, but you didn't really know what you were doing, but you really impressed upon me that you were willing to learn.

Randy Shoup:And, so I liked your attitude.

Bryan Cantrill:I thought that's great. Yeah. I mean, that's that's important. And so what did you do for Intel? Were you because you were at Intel for a couple of summers.

Bryan Cantrill:Right? A couple

Randy Shoup:of summers. Yeah. I worked, I worked in a mask shop. So for you guys know, I know. But for the others, a mask is the, for to make semiconductors, you need this big glass plate that you write you draw the outline of the circuit on there and then you shine the now it's X-ray light, but then UV through that thing and it makes a shadow and it changes the chemistry of the thing you're writing on, and then you etch it away blah blah blah.

Randy Shoup:Anyway, so Underneath.

Bryan Cantrill:For those of you who are looking to learn more about either the the photo lithography or then e v it's e v lithography and e v lithography. Yeah. I'm sorry.

Randy Shoup:No. No worries. Anyway, so yeah. The, so the mask shop Intel did that in in the house, you know, and it was a pretty small group, and they needed people to write software tools to help them do statistical process control for, for the machines, and just a bunch of software tool you know, just a bunch of software tools. So it was I got a lot of playing around with Oracle databases and writing, yeah, writing queries and graphs and so on for the technicians and the engineers to do their job.

Randy Shoup:So, I had a great time. And it was a great group of people, really, really fun. So I did that after sophomore summer, then after junior summer, and then I actually worked part time as, like, a flexible work hours employee, like an actual part time employee, not an intern or, for senior year. So I I would take classes, Monday, Wednesday, Friday at Stanford, then I would drive down to Santa Clara to, work Tuesday, Thursday all day.

Bryan Cantrill:And at what point is law school beginning to lose its appeal?

Randy Shoup:Oh, not yet. Not yet. So I actually Okay. What? Okay.

Randy Shoup:So, very briefly. So let's say I graduated. I did not wanna go straight to law school because most people don't. So I worked for Oracle, for two years as a software engineer. That was great.

Randy Shoup:Had a great time. And then much to the chagrin and surprise of my compatriots and manager, I'm like, okay, now is the time to take the GRE and the LSAT and, you know, get all set to go to law school and international relations school. And everybody looked at me like I was crazy. And I said, hey, I've been telling you for two years. This is what's gonna happen.

Randy Shoup:So I

Bryan Cantrill:So, again, we wouldn't take you seriously, obviously.

Randy Shoup:I should I should I should be taken most seriously and literally when I when I tell you when I tell you that. Anyway, so, yeah. So, apply to, law school and international relations school. I end up starting a program which is a joint Stanford Law, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, master's. Normally, three years plus two years.

Randy Shoup:If you combine it, it's four. So I started and the way that you do it is you do like a year of law school, then a year of the IR school, and then back and forth semester by semester. Wow. Anyway, so I so I did the first, I did the first year at Stanford Law School. It was fine.

Randy Shoup:And then I took the took an, they would call it a summer associateship. So, you know, an internship for law students over the summer, and it should have been the perfect job, and I hated it. So it was the small office in on Sand Hill Road, of a so a big New York firm called Weil, Gotcha, and Manjos, a tiny, Silicon Valley branch office that did what's called patent prosecution, which is getting people patents. It's not about suing.

Bryan Cantrill:Oh, yeah.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. And so what I I thought it would be and again, on Silicon Valley Road, I was on a Sand Hill Road, like, right next to all the VCs at that very last right before 280 on the right hand side when you're going north, that whole complex there. It's a bunch of VCs that are still there.

Bryan Cantrill:Anyway, that's KP is still there, but a bunch of them are still right

Randy Shoup:still right there. There you go. I've I've visited several Sharon Heights.

Bryan Cantrill:Long time. Heights Shopping Center. I know it. I'd say it's like the waiting room for Silicon Valley. It's Starbucks in the Sharon Heights.

Bryan Cantrill:Even shopping center.

Randy Shoup:Even farther away. So, like, really right in the very if you're go from Sharon Heights to 2 I know.

Bryan Cantrill:I know. It's just it's like literally there is no retail establishment between Sharon Heights and those offices at the intersection of San Diego.

Randy Shoup:It's a view. Because it's all, like, VC, VC, VC, VC. Firms.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Exactly. Yeah.

Randy Shoup:Anyway, so, small office. It was casual dress, which was very unheard of for people in, lawyers in 1993. But, you know, hey, our clients were dressed in business casual. So we were too. Really liked the attorneys, but I just hated every minute of getting people patents.

Randy Shoup:And what so anybody who's been involved in a patent on either side, it is it is the inventor is up there on the whiteboard describing his or her amazing invention. And the lawyer is a scribe who writes down diligently all the things that the amazing inventor has invented and then does bureaucratic infighting with the patent office to get a patent. And so every moment, it was so painful for me to be sitting at the conference table looking at somebody designing or outlining their design on the whiteboard where it's like, I wanna be that person. I don't wanna be this person. And, that was a big, soul searching for me that summer because, hey, I've been telling people and myself wasn't lying.

Randy Shoup:I didn't think so. For ten years, this is what I wanna do. And, oh my god, I now I have exactly what I've always wanted, you know, the combination of the two interests and I hated it. So I'm immediately thinking, okay, well, what if I finish up law school and IR school, I go in house at a technology company, maybe in ten years they give me a technology group to run, and I'm like, oh my god. You're an idiot.

Bryan Cantrill:You can't cut whoops.

Adam Leventhal:I, you know, I didn't

Bryan Cantrill:wanna I I didn't wanna put my thumb on the scale on that one, but No.

Randy Shoup:No. No. Anyway, long story short, it's you know, it was so obvious what needed to happen, but it took me a long time to get comfortable with it, if that makes sense. So, yeah, so I never so I never went back. So I, you know, I I stopped out as Stanford says, never finished the never went to the, Johns Hopkins.

Randy Shoup:I never never completed law school. And I have never once ever regretted that decision.

Adam Leventhal:I would say this sounds like the most successful internship I've ever heard of.

Randy Shoup:Oh, my God.

Adam Leventhal:To provide absolute life clarity.

Randy Shoup:Life clarity internship. And Adam Adam, to your exact point, if it had been anything else other than the otherwise perfect job on paper and after my first year summer, I would have continued on because, like, oh, it is a formal dress or, you know, whatever. Right. Right. Right.

Randy Shoup:Right. Right. Right. Right. Right.

Randy Shoup:It was it's a big firm that's all faceless or, you know, tick, tick, tick. I, you know, I would have looked for just because, you know, I'm a human. Like, I I had this plan. I was gonna execute the plan. So, yeah, all, if it had been anything other than perfect and early.

Randy Shoup:Because the other thing is, like, oh, this my whole life is gonna be terrible, but, hey, I'm already halfway through the program.

Bryan Cantrill:Some customers.

Randy Shoup:I may as totally, totally I've already done

Adam Leventhal:this for a year and a half, so I might as well spent the next thirty years on this.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Well, yeah. And there are a lot of people that come out of law school and never wanna practice and don't. And, you know, you can do other things. But but it would have been hard for me to go back to being a software engineer, which I did do.

Randy Shoup:So I, I finished that up, and, I went and begged for my job back at Intel. And my great friend and mentor, Girish Pancha, who just retired from being CEO of StreamSets, Welcome you back with open arms and,

Bryan Cantrill:At Intel. So you you were

Randy Shoup:No. No. At Oracle. At Oracle.

Bryan Cantrill:At Oracle. Yeah. Yeah. I actually I was gonna say, I couldn't tell if you're being sarcastic or not about your time at Oracle, but it sounds like that was not sarcasm that that

Randy Shoup:that No. Oracle. So

Bryan Cantrill:so It was it's okay. You're in a safe space. You we we you know, we can accommodate all Make

Randy Shoup:it safer, Brian. Make it safer. There are there are Yeah. So it is both true

Bryan Cantrill:We can get all this out.

Randy Shoup:Oracle overall. It it is both true that Oracle overall, even at that time in the early nineties, was, you know, you don't wanna be a partner with them. I I I have a sidebar to say about making your customers your enemy and is that a really good business strategy? But I loved my little group. So, all of them were all of them were great friends.

Randy Shoup:You know, they were all groomsmen in my wedding and, like, my best friends, for what's this now, thirty five years, are all the people that were on Team Browser. And so we built a, this is before Web Browser, so that was only '95. This was 1990. We built a ad hoc query tool, which was called Oracle Data Browser.

Bryan Cantrill:And,

Randy Shoup:it was, it was all bitmap graphics, and you used, you graphically built your query out of little boxes and lines. You know, imagine an entity relationship diagram, and then it was a spreadsheet output.

Adam Leventhal:So it was Freddie, when you bring this home and show it to your dad, it's like That did he laugh. I mean, yeah. It's like Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:Yeah. Look. We look.

Adam Leventhal:I I our intern at PARC did that. You know?

Bryan Cantrill:Right. Yeah. Twenty years ago. I feel like I'm looking ten years into the future. No.

Bryan Cantrill:I don't. No. I don't think I was in. I mean,

Adam Leventhal:ten years into the past. Excuse me.

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Right? Yeah. Because right. So, let's see.

Randy Shoup:That was so I graduated That

Bryan Cantrill:was very forward looking, honestly. I the the because that isn't so you said that was in 1990. So that is in Yeah. And Oracle was a much smaller company then. This is like a It was.

Bryan Cantrill:How many employees were at Oracle? I mean, this is, like, probably

Randy Shoup:less than I'd have to look. Thousands. Maybe less than 10,000. Probably less than probably less than 10,000. Yeah.

Randy Shoup:That's probably about right. Yeah. Yeah. The funny thing about, going to work for Oracle in 1990 and graduating from Stanford then is I hope they have changed this policy. But at the time, the policy was, Oracle only only hires from these whatever eight schools, and you can imagine what they are.

Randy Shoup:And they the the very explicit recruiting strategy was we will hire smart people no matter what, and we'll put them in any place that they're willing to do the job. So I had it was well known and well, leveraged among my graduating class that, like, if you had a heartbeat in a Stanford degree, you could work at Oracle. So Oh, interesting. So there was a part of me okay. And, you know, I had people who are, like, amazing people in my poli sci classes, like, totally amazing people now in the school now in actual foreign service.

Randy Shoup:Oh, yeah. Receptionists at Oracle. You know, it was their first job. And, so that was actually a potential downside for me because it's like, hey. We devalued this whole thing by, like, anybody from Stanford could come here.

Randy Shoup:But, I made myself feel good, and it was actually true that they actually for the engineering group, it was, like, a little more rigorous, if

Bryan Cantrill:that makes any sense. Well, I mean, this is just in general true at Oracle. But the closer you are to the database, the more technically interesting it is. And so, you know, that is their their core product. And I think especially that time, that

Randy Shoup:Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:What you were up to, I mean, that's is, that's and so so you all make this kind of graphical data browser that, again, is, like, is ahead of its time. And when you kind of so you you're able to get your job back at Oracle. And then how long do you stay how long do you stay there?

Randy Shoup:Yeah. I was there for a total of seven years from 1991 to '97. And you can forget about the year I was away, I suppose, at law school. And yeah. And so, after that, I went to a company called Tumbleweed, which did, security software, worked there ultimately as chief architect and a technical fellow for about six years, brief stint at Informatica, which does, you know, data warehousing, etcetera, data integration.

Randy Shoup:And then I joined eBay for the first time. 02/2004 to 02/2011, I worked as an individual contributor on eBay's real time search engine. So at the you know, now real time search, you get that for free with Elastic. Everybody has it. It's easy.

Randy Shoup:It nobody, as far as I can tell and find, nobody was doing real time all in memory search in, 02/2004. So I didn't invent that, but I got

Bryan Cantrill:about that era because in so we we obviously go to the .com boom and bust

Randy Shoup:and Oh, yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:I mean, in the the bust was a thermonuclear event around here. I mean, it was a It was

Randy Shoup:very busty. It

Bryan Cantrill:was very deep.

Randy Shoup:Yeah.

Bryan Cantrill:And I mean, I was you remember the the you remember that excited home facility on the 101 that went from, like, absolutely nothing, went from, like, wetlands to a a new construction to full parking lot to empty parking lot with, like, rocks thrown through the windows to add to abandoned all within, like, eighteen months. Yeah. And then it was it was abandoned for a long time before it ultimately became, I think, a Stanford building. But they

Randy Shoup:Yeah. Yeah. I I so I I blew past that in my so I was a tumbleweed through the through the up and the downof.com. So, again, that's 02/2000.

Bryan Cantrill:And did you think about, like, at that point, do you or or do you just know so resolutely something I knew resolutely then that, like, this industry is my this is my calling. Like, I'm not there's no amount of bust that's gonna get me to do something else.

Randy Shoup:Oh, yeah. I never I yeah. I was loving I was loving doing, you know, being an individual contributor and Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Randy Shoup:My leadership. Our traffic was, like, so much better